It was while visiting the graves of my parents and sister one day recently at White Haven Memorial Park in Pittsford that I noticed a monument called “Memorial to the Four Chaplains.”

It’s a tall, stone obelisk. Around the base, etched in stone, it tells this story: In World War II, when the troop carrier on which they were sailing to Greenland was hit by a Nazi torpedo, four U.S. Army chaplains of different faiths—a priest, a rabbi, and two Protestant ministers—voluntarily gave up their life vests to soldiers who had none and together went down with the ship.

(Photo by Elisa Siegel)

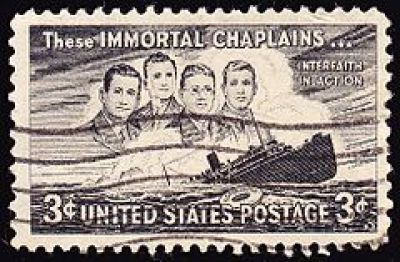

Our parents’ and grandparents’ generations knew all about the Four Chaplains. Accounts of their heroism by sailors who had survived the sinking were widely reported. Each chaplain was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Purple Heart. A U.S. postage stamp was issued in their honor. Each of them was awarded a special Congressional Medal of Valor. At the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., at the Pentagon, and in more than a dozen cities across the country, memorials—stained glass windows, monuments, whole chapels—were dedicated to their memory. In Rochester, dignitaries including Sen. Kenneth B. Keating, R-N.Y., spoke at the 1959 dedication of White Haven’s Four Chaplains Memorial.

And yet, when I’ve recently mentioned the Four Chaplains to friends, I haven’t found a single person who knows the story. I, myself, didn’t know it until I stopped that day at White Haven to have a closer look at the memorial.

So, let me take a moment to tell the story this Memorial Day, drawn from sources provided by the Four Chaplains Memorial Foundation, historical documents of White Haven, Congressional testimony of survivors, various Wikipedia entries, and No Greater Glory (Random House, 2004) a book about the chaplains by former Washington Post foreign correspondent Dan Kurzman.

To my mind, the heroism of the Four Chaplains carries a message that may be of special value to our nation, which today feels increasingly torn apart.

The U.S. Army Transport ship, Dorchester, was an aging, luxury passenger liner that had been converted to transport American soldiers during World War II. On one such voyage, sailing from Boston on Jan. 23, 1943, it carried 904 passengers—mostly Army but also Navy, Coast Guard, Merchant Marine, civilians with the War Department, and crew. The destination was Greenland. Troops were needed there to operate airbases, radar stations, and weather stations.

(At least one soldier on board was from Rochester: Seaman First Class Richard B. Streicher, age 26. According to 1940 Census records, he had lived with his parents, Edward and Anna Streicher, and older siblings, Elmer and Beatrice, at 340 Rosewood Terrace in southeast Rochester’s Beechwood neighborhood.)

Accompanying the troops on the Dorchester were four Army chaplains. Their job was to look after the troops on the dangerous voyage in the North Atlantic, boost morale and provide spiritual support and counseling.

Two of the chaplains were Protestant: George Fox, 42, a Methodist minister, married with two adult children; and Clark Poling, 32, a Dutch Reform minister in Schenectady, married with one young son (his wife was pregnant with a daughter who would be born three months later). The third chaplain was Rabbi Alexander Goode, 32, married and with a 1-year-old daughter. The fourth chaplain was John Washington, 34, a Catholic priest.

The four chaplains knew each other before they boarded the Dorchester. At a U.S. Army Camp in Taunton, Mass., a staging area for troops departing from Boston, they’d met and become friends. Once aboard the Dorchester, they bunked together, ate together with the troops, organized a variety show—and conducted services attended by soldiers of their own as well as each others’ faiths.

The Dorchester’s passage in the dead of winter through the North Atlantic was rough. Ten days of storms and violent seas left many of the troops seasick and exhausted. Then, with just one more day to go, they entered what was called “Torpedo Junction”—an area where many Allied ships had been sunk by so-called “wolf packs” of German U-boats. With daylight they would be close to Greenland and safely under air cover from an American base there, but weary of the U-boat danger overnight, the captain ordered troops to sleep in their clothes and with lifejackets close at hand.

They nearly made it, but at 12:55 a.m. on Feb. 3, a U-boat fired four torpedoes. One hit, exploding in the Dorchester’s boiler room. The blast destroyed the electric supply and released clouds of steam and ammonia gas. Many troops, trapped below deck, died instantly. Others, jolted from their bunks, groped and stumbled their way up to the decks. Taking on water rapidly, the ship began listing. Overcrowded lifeboats capsized; rafts drifted away before anyone could reach them. One survivor described a scene of “hysteria” and “utter confusion and disorder.” Some men clung to the rails, frozen with fear, unable to let go and plunge into the dark, freezing water.

It would take just 27 minutes for the Dorchester to sink.

But amid the chaos and fear, were Chaplains Fox, Poling, Goode, and Washington. According to survivor testimony, they were a steady source of order and hope, calming disoriented and terrified men, guiding them to their boat stations. They opened a storage locker and distributed lifejackets. Then they coaxed sailors, paralyzed by fear, to jump into the sea. When the supply of lifejackets was exhausted, several survivors reported watching in awe as the chaplains each either gave away, or forced upon others, their own.

From sworn affidavits, here are some of those accounts, in the voices of actual survivors:

“Up to the very last minute (the chaplains) continued with their mission of healing and comforting the terror stricken.” – Frank G. DiMeo

“I made for the life raft to which I was assigned and … passed four chaplains. … One of them possessed a life jacket and the other three did not. As I passed I noticed the chaplain with the life jacket remove his jacket and give it to a soldier … who did not have a life jacket. I overheard the soldier say, “Thank you, Chaplain.’” – Joseph D. Haymore

“They were passing out life preservers from boxes on deck. When these were gone, I saw them take the life preservers from their own persons and hand them out, too.” – Oswald R. Evans

“From my position as I clung to (a) lifeboat, I saw the chaplains clearly standing at the rail of the transport minus their life jackets, urging men to leave the ship with disregard to their own safety.” – William J. Pantall

(A)s I left the ship, I looked back and saw the chaplains … with their hands clasped, praying for the boys. They never made any attempt to save themselves, but they did try to save the others.” – Grady L. Clark

“I saw these chaplains without life preservers kneeling on deck and praying for us.” – Kenzel L. Linaweaver

“The last I saw of the chaplains they were standing on deck praying. By that time the ship had capsized and was at a forty-five-degree angle.” – Anthony J. Povlak

By multiple accounts, the chaplains clasped their arms together as the slant of the deck became severe. And just that way, with their arms linked and their heads bowed in prayer, they sank beneath the waves.

On that night of Feb. 3, 1943, when the Dorchester sank 150 miles off the coast of Greenland, 672 men died in what was one of the nation’s greatest maritime losses during World War II. Many of those who did manage to jump from the ship died of hypothermia within 20 minutes—the water temperature that night was 34 degrees Fahrenheit. All life vests were fitted with a blinking red light meant to help rescuers locate sailors in the water. But when a rescue ship finally did arrive—nearly an hour after the sinking—what it found was mostly a silent sea of hundreds of blinking red lights, each one marking the body of a brave American patriot no longer in need of rescue.

In later testimony before Congress, one survivor, Benjamin Epstein, reflected on what he had seen:

“To take off your life preserver, it meant you gave up your life. You would have no chance of surviving. They (the chaplains) knew they were finished. But they gave it away. Consider that. Over the years I’ve asked myself this question a thousand times. Could I do it? No, I don’t think I could do it. Just consider what an act of heroism they performed.”

( Photo by Danielle E. Thomas/Washington National Cathedral)

I’m nearly twice as old as the average age the chaplains were when they died. When I was younger, I certainly would have admired them for their bravery and sacrifice. But now, with age, I’m even more in awe.

The longer we live, the more we see how complicated life can get, and how many ways there are to avoid the hard choices. Chaplains Poling and Goode, for example, could have reasoned, “We have wives and young children at home who depend on us. We should save ourselves for their sake.” Chaplain Washington could have calculated that by staying alive to serve his parish, he could help many more people than the one sailor he might save with a life vest. All the chaplains might have told themselves—truthfully—that most of the troops left on board, hysterical and frozen with fear, were beyond saving.

But none of them took those outs—or a dozen others we could probably think of. Instead, until the end, they did their duty: to serve, to guide, and to comfort those in their care.

And during their service, they treated each other and all the troops in their care without regard to differences between them. In the chaos after the torpedo struck, no one reported hearing a chaplain ask a soldier, “Are you Catholic? Are you Jewish? Are you one of mine or one of this other chaplain’s?” They each helped everyone equally.

The “content of their character”—to use Martin Luther King Jr.’s phrase—was clearly revealed by what each chaplain—Fox, Poling, Goode, and Washington—did in those last 27 minutes of their lives.

This Memorial Day, we’ll all have many choices as to where to go to honor those who gave their lives for our country. Some may go to a Vietnam War memorial, others to the gravesite of a loved one. But I encourage you also, if you have the time, to visit White Haven Memorial Park to remember and to honor the Four Chaplains, and to think about their devotion to duty, their sacrifice, and their focus on our common humanity, rather than the differences that divide us.

Peter Lovenheim, journalist and author of “In the Neighborhood” and “The Attachment Effect” is Washington correspondent for the Rochester Beacon. He can be reached at [email protected].

Peter,

I thoroughly enjoyed your article. We, as a society need to be reminded of the heroes that this country sorely needed during those times as well as today.

Thank you,

Johnny Skelton, American Legion, Department of Texas, District 13, Post 169 Wichita Falls, Texas

Thank you for this post, Peter. The Four Chaplains are no doubt honored by your compassion and insight.

I have seen that monument at White Haven but never took the time to look into it further. Thanks for bringing it to our attention. It’s a remarkable story that needs to be told and retold.

I have only the vaguest recollection of this history, and had no idea there was a local memorial. Thank-you!

Peter, send this piece to the New York Times, send it elsewhere, send it where it an be read by legions. Beautifully done, and wonderfully pertinent.

Oh, Peter, what a deeply moving essay. I echo Sandy M’s comment. Well done – you have truly done a good deed to bring this sad saga to light for us today.

Many, many thanks.

Sorry – typo – deeply moving, not “reply moving”…

Peter…

A most moving and inspirational article! Being a war baby, I’ve always known of them but will make a trip out to White Haven.

Thanks,

Sandy Mayer