Rochester has long claimed an identity as a city of the arts. Others, too, have labeled us as one of the most vibrant arts communities nationwide. Yet a new exhibit highlights challenges and raises questions about the support provided to working artists here.

“State of the City” opens Oct. 4 at Rochester Contemporary Art Center. Part of the collaborative program Current Seen, the exhibit presents several artists’ perspectives on the present and future of Rochester. It asks questions about the state of the city—and about the state of the city for artists.

Members of the arts community involved in the exhibition—who have experience working in small organizations or independently—point to obstacles artists here face in making a living, resources they rely on as they train and start their careers, barriers to access in the arts, the role of arts administration in a flourishing arts scene, and the need for more in-depth media coverage of the arts.

Can Rochester draw upon the observations of people in the field to make sure that work in the arts is supported and valued?

Making artists’ work sustainable

One of the projects featured in “State of the City”—the “Artists Sustainability Survey,” organized by Rochester artists Reb Ayşe Geduk , Gary Lamaar, and Ray Ray Mitrano —directly addresses the challenges local artists face in making a living.

The group project surveys “working artists in Rochester on their value in pay, community relationships, space accessibility, and overall experience in our creative workplace,” the project’s tumblr page says. This engagement has produced a growing online archive of interviews with local artists.

The survey was featured on a WAYO 104.3 show hosted by Mitrano, a social artist and activist, in which he interviews Lamaar, a musician and composer, and Ayşe, a multi-disciplinary artist.

With some variation in wording, the survey asks artists questions such as:

- What type of arts work do you do?

- What is your time worth?

- Do you feel compensated for your arts work time?

- What are others being paid for similar work?

- How frequently are you asked to do work without pay?

- What’s the longest you’ve ever had to wait to get paid?

- Do you ever ask for more pay? How do those conversations go?

- Do you feel safe and respected in the spaces you’re working in?

- Would you say that your work spaces reflect the surrounding community?

- Do you feel an art workers’ union or association of artists would be beneficial?

The survey provides a space where artists can share experiences and strategies for dealing with the unknowns of compensation—and where non-artists (including local officials) can become better informed about problems specific to working in the arts.

When asked about what other artists are being paid for similar work, Ayşe expresses a lack of clarity that many of us can likely relate to in our own workplaces: “It’s kind of a mystery.”

In the sampling of interviews I listened to, all of the working artists also had other jobs—some art-related, some not. They were all young. They talk about wages and issues around hourly pay: Ayşe points out, for example, that hourly teaching jobs tend not to account for prep time or help provided to students after class. Artists also describe problems they’ve encountered in negotiating for pay and actually getting paid, including situations where potential employers expect them to work just for exposure or offer vague terms, or where they face bureaucratic obstacles to timely compensation.

Mitrano describes situations where nonprofit organizations with “the ability to fundraise tax-deductible donations” and “businesses who bank on arts and culture, especially bars and restaurants” neglect to budget for and pay artists.

“If you want arts work,” he says, “then you need to pay the arts workers.”

The project’s memorable acronym, ASS, is a comment on this problem: “We have a status-quo culture of businesses, organizations, and municipalities expecting free labor from the creative economy. Stop making asses out of yourselves and pay Rochester’s arts and culture workers for their time whenever you engage them.”

The survey also contains musicians’ accounts of how they get paid (or not) for performances. Lamaar points out that original songs tend to be paid less than covers. One of his albums is titled “Self-Love,” and his bio on the RoCo website cites the importance of “themes of freedom and self-worth.” When the value of arts work is ambiguous and the best-paid gigs are derivative, creative freedom and a sense of one’s worth may be questioned rather than assumed. The survey’s exploration of economic and cultural barriers that artists face points toward a struggle for these ideals, among others.

Lamaar also speaks about the divide between art spaces and surrounding communities in the survey and urges further discussion: “Rochester’s a very segregated place,” he says. Referring to the Eastman School of Music’s location off Scio Street, which, if followed in a northeast direction, leads into his neighborhood in the Carter Street/Portland Avenue area, he observes a divide between the school and the neighborhood: “Scio is Scio, and Eastman is Eastman,” though “conversations around that are happening.”

Not a survey designed for data-collection purposes, Mitrano says the project is more focused on starting discussion of important questions. The group plans to move the conversation forward by “organizing funds to pay Rochester artists to survey their own social circles.” A long-term goal is “collective solidarity and action for a more equitable Rochester arts and culture workplace.”

Given people’s general hesitancy to talk about how much they make—out of a sense of politeness, embarrassment, or fear of reprisal by an employer—it’s significant to see artists stepping forward to talk about money in a public way. Participants in the survey document issues that have been obscure within and outside of the arts community, building solidarity in the process. The project also suggests transferrable methods that workers in other fields—who, like Ayşe, believe “I deserve to be able to work and live”—might consider as they try to pin down and assert the value of their work.

Providing a framework for artists

The experiences of an artist who grew up and pursued his arts training in Rochester and now lives in Brooklyn offer another avenue of learning. David Hammond’s project “Flower City Crescent,” also featured in “State of the City,” documents the natural environment and cultural landscape around the Genesee River gorge and the Saint Paul Boulevard neighborhood. Hammond describes the important roles that access to nature, school art programs, and supportive community members played in his development as an artist in Rochester.

Hammond’s interest in the natural environment began with his grandmother’s resourcefulness.

“I grew up on the northeast side, and we didn’t really have a whole lot,” he says. His grandmother would take him and his two brothers on trips outdoors and “show us the plants that were around when she was young and the native species (and) what you can eat.” By picking berries and other plants, they supplemented their diet.

“Being able to go outside was a huge resource,” including watching people fishing in the river, Hammond adds.

Hammond’s grandmother served as a radio technician in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II and bought a home in Webster through the GI Bill. She moved to the city after leaving an abusive marriage and struggled with poverty, applying her skills to factory work.

“She had a fighting spirit,” Hammond says. “She never took ‘no’ for an answer; she’d find a way around things.”

She extended this spirit to her community.

“I think through her experience she was always aware of other people’s suffering and social issues,” he says.

His mother shared this awareness and, interested in working with kids in the city, she graduated from Nazareth College with a sociology degree. She became unable to work, however, due to the effects of childhood trauma. Hammond and his brothers lived in foster homes for periods of time. They took turns living with their mother or grandmother, who took them to parks, free and accessible without a car.

“They both had experiences living on farms as children, and they saw the value of being connected to your food and being connected to your natural environment,” he says.

Their perseverance and empathy supported Hammond’s development as an artist and continue to influence his approach to art.

Trips to the library were also important, and Hammond notes that the art and photography books at Rochester’s central library rival some of the collections in New York City. Parks and libraries provided artistic inspiration to Hammond and his twin brother, Jonathan. His brother was drawn to Audubon and other nature books, using them as a basis for drawings. With a digital camera he received from his foster mother, Jonathan would also take photographs of nature during the brothers’ visits with their grandmother. When Hammond was 14, he found a working film camera in the garbage in front of a house on Ridge Road and followed his brother’s example.

Hammond’s interest led him to study photography in high school in Brockport, where his foster family lived. He was able to take a number of art courses and use the school’s excellent darkroom and digital print center. He considers himself “very lucky to have had such a nice resource” and expresses concern that “art programs are becoming increasingly rare in public schools.” Now working as a freelance photographer and assistant editor in New York City, he’s “finding that having that foundation is vital—(it) separates me from people … who weren’t fortunate enough to have that in their career.”

In addition to access to art classes and spaces, artists rely on educators and other supporters.

“(W)hen I talk to artists way more successful than I am,” Hammond says, “they all credit an art teacher or librarian or somebody who saw their potential and laid the framework for them to start out as an artist.”

His teachers at Brockport encouraged students to attend free art openings in the city, through First Fridays. Seeing his photographs, they encouraged him to make a portfolio, which in turn helped him get into Rochester Institute of Technology.

Hammond had help from his high school guidance counselor and social workers from the Villa of Hope as well. RIT professor Susan Lakin mentored him and helped him stay in college as he dealt with the lack of a “framework for where to live during school breaks and how to fund going to school,” including the cost of art supplies.

“All of these roles are integral,” Hammond says. “I wouldn’t have done it at all without there being that community.”

A supportive community and adequate resources for arts programs were crucial as Hammond pursued his training in the arts, graduating from RIT in 2012. But finding jobs in the arts locally was difficult.

“After college I had a tough time,” Hammond says. “I didn’t get employment right away, and I had to work in area factories in Rochester, under temp agencies.”

Attending First Fridays helped him stay connected to art.

“I’d go to VSW (Visual Studies Workshop), RoCo, the Hungerford Building, Anderson Alley, all these areas,” Hammond says. “I would actively be engaging that part of my brain even though I wasn’t working within it.”

He moved to New York City in December 2014, where, he says, there are “a lot of (photography-related) jobs. … There’s a revolving door, so you can always find employment.”

“I sometimes wish I would have stayed (in Rochester) and just fought it out,” Hammond says. At the same time, he wanted to expand his knowledge and experiences in the photography world. Brooklyn and New York have provided that.

While seeking opportunities and expanding his experience in New York City, Hammond has remained focused on Rochester as a subject of his art and on access to art opportunities for kids here. He has presented to students at the Flower City Arts Center and city schools.

“I was talking to these students that don’t have the resources that I had when I was in high school. So, I want to do whatever I can to make sure they can have that. It’s something that keeps me up at night,” he says.

Due to obstacles Hammond faced growing up, “focusing in school was very difficult, but I was able to focus on art because (it) tapped into other things that just made sense to me and were transcendent of my situation,” he says.

Hammond believes Rochester could benefit by funding art programs in high schools and art programs that target a larger population of the city. He notes that programs at Flower City Arts have inspired kids to become professional photographers, and he hopes the program can grow to include more students. Hammond also hopes educational programs in Rochester, including ones not directly related to the arts, can communicate more with each other.

He’s observed that for jobs as “an assistant or a tech in the photography world, it helps to know a lot of different things. In any job, the more diverse your understanding and training, the better off you are, and you can help each other out more that way.”

Hammond also sees opportunities to expand the audience for art events.

“When you go to an art show, you want the demographic to replicate what the city is,” he says.

Access to transportation is important, and Hammond admires artists who “take their exhibition into as many communities as possible.”

He would like to do an exhibition at a laundromat, for example—“a communal space” with “open walls”—or a barbershop or salon.

He shares his art in the communities where he works.

“Anywhere I photograph I give prints out, and I’m making a book, a little chapbook or artist’s book, to hand out to people in the immediate area,” Hammond says.

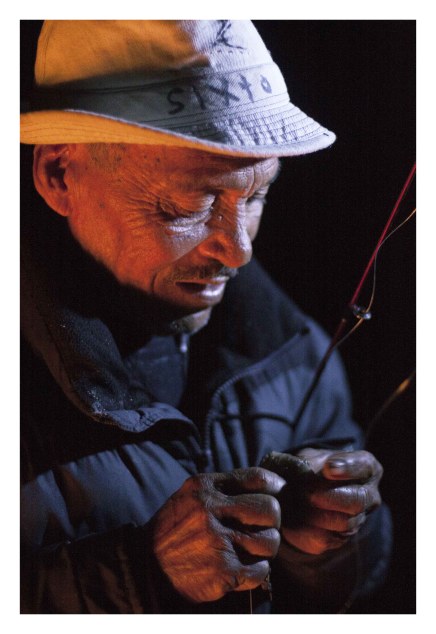

Hammond and Richmond Futch Jr. —whose charcoal portraits of members of the homeless community, a community he has worked with for many years, will be exhibited in “State of the City”—will be speaking about their work at an artist talk at RoCo on Oct. 5 at 2 p.m.

Drawing on expertise

The arts community extends beyond artists themselves, and the viewpoints of arts administrators are also important to understanding the resources needed to sustain and grow the city of the arts.

Claudia Pretelin, who was gallery associate at RoCo before moving to California in 2018 and is back in Rochester for several months to help organize Current Seen, has worked in arts administration here, in Los Angeles, and in Mexico City. She observes that in all three cities, the lack of resources has been challenging.

“Sometimes the work that nonprofit organizations have to deal with is accomplished by two or three staff members and the work and support of many interns and volunteers,” Pretelin says.

Her commitment to RoCo and to a contemporary art gallery in Los Angeles is rooted in appreciation for how they “find ways to partner and help each other to make the arts thrive and to be accessible for different audiences.”

RoCo executive director and curator Bleu Cease hopes to clarify the work that curators are doing around the city to help artists thrive.

“The act of curation, the process of bringing together various different components to support an artist in their display, the expression of their ideas and their project, bring it to fruition and share it with the public: this is a lengthy, complex process,” Cease says. At a time when the term curation is used casually—to refer to a person’s arrangement of photos on social media, for example—he emphasizes that it is also “a career.”

Cease stresses that acknowledging expertise in the art world is not about “creating barriers to entry for artists, for administrators, for curators, for youth who want to get involved in the field.” Professional curators take many paths to the field, he says, including activism and working as artists; their background is not exclusively academic.

Cease describes the Rochester 2034 comprehensive plan as an example of “a tendency in this city to not adequately employ the expertise from this field.” He says that while the city relies on seasoned experts on education when it develops education policy, it does not look to experts in the arts in a similar way. He thinks members of the arts community were able to express this concern during the public-engagement process that followed the draft plan’s release.

But he points to a conflation of expertise and appreciation when it comes to the arts.

“We’re thinking of it as a hobby,” Cease notes. “We’re thinking that the city staff person who likes the arts is equally an expert as the museum director who’s worked in Rochester for 30 years, and that is a misstep.”

He urges local government to listen and to recognize grassroots and small-scale efforts more.

“For this art community to continue to grow and progress, we need municipal support at a whole other level,” he says, “Studios, independent curators … are working incredibly hard to build the art community here. … They need to be more fully recognized and supported, in part by visitors and patrons, but also it’s critical that the city government understand what is happening.”

And not just city government. RoCo has invited the candidates for county executive to meet with the arts community; a forum with Adam Bello has been scheduled for Oct. 7.

Dawn Lipson, chair of the Arts and Cultural Council for Greater Rochester, has also described a need for more support of the arts. In a 2017 blog post, she wrote: “Individual organizations in Rochester receive some funding from the City of Rochester and the County of Monroe as well as the State of New York and we are grateful for that support but it is not anywhere near what it needs to be. The economic impact of the arts on our community is clear. The quality of life in our community is intertwined with the vibrancy of our arts community and is frequently cited as a reason someone chooses to live here.”

Added Lipson: “Rochester, the City of the Arts, is a fertile ground for the Arts to grow and flourish and with additional support the entire community could soar.”

Bringing issues to light through writing

In addition to funds, support could come in the form of written words. RoCo will host a panel on Oct. 24 about the “The State of Art Writing ” aimed at encouraging more varied and nuanced discussion of the arts locally.

Sarah Webb—a writer, curator, educator, and artist with over 25 years of experience in the local art community—will moderate the panel. She describes art writers as educators who “make what might seem at first uncomfortable or unfamiliar accessible, worth a first (and maybe another) look.” In addition to introducing and providing a framework for encounters with art, they encourage critical questions such as “Whose story is being told, whose story is silenced, and why does that matter?”

Webb would like to see more art reviews and writing about art on social media as well as stories about art in different neighborhoods, artists who are less well-known, innovative art spaces, and how works are commissioned, among other topics.

Like the Artists Sustainability Survey, Webb focuses on questions, showing how writing can push thinking in new, challenging, and productive directions.

“Can we have a deeper conversation about what is involved in creating work, and make the necessary expenditures more transparent to a greater, or different audience?” she asks. And “as this (art) community fabric becomes ever more vibrant, how can artists and writers be fiscally valued for what they offer and provide to the community?”

Questions about the value and sustainability of arts work in Rochester are difficult ones. As Webb says, “there are greater structural, systemic and institutional issues at play not just in the arts, but in the makeup of our entire country.” Artists and writers, though, “have the power to disrupt, to create fissures, to bring such issues to light, and that in itself can begin change.”

Esther Arnold is a Rochester Beacon contributing editor.

Some of us have rehashed variations of this conversation for nearly 50 years. There were no easy solutions then as there probably aren’t now. I can only offer what I WISH we had done in 1970, 1980, 1990…

FIRST, the County, City, Finger Lakes Region of NY must decide to work together, raise big bucks and to put us on the WORLD VIEW MAP . (See Tulsa, Okla. plan to create an “Art Corridor” working across state lines as one example.) Without major commitment — translate: money and power — we can all simply stay home.

1)Initiate a truly world class Community Art School. There are a few places to investigate..Woodcraft in Maine, Penland in N.C., etc. We have several unique talents here: CRAFTS, PHOTOGRAPHY and MUSIC — a base that provides the envy of most national and even international regions. Capitalize on them! (Again, infusion of big money to create and sustain.)

2) A social safety net for full-time artists. Free or nearly free health care insurance, very low cost studio space, centers for materials exchange. Interest free mortgages to purchase housing – especially in distressed areas. (Revisit the programs that saved the South Wedge in the 1980s.)

3) Years ago, big dollar prizes were handed out at competitive exhibitions. Bring that back and/or initiate fresh.

4) Be brave and be tough. No tepid efforts…no protectionism…backing of government, educational institutes and industry a must!

First, let’s separate the value of art from the value of creating art. The value of art is in the eye of the beholder. The value of creating art is the value of supporting an individual or family, the value of teaching art technique to current and future generations, the value of a multiplier effect when an artist purchases his/her needed raw materials, the value of a contributing member of society — all of which warrants community support. In that government taxation is a measure of community support, it’s time to lobby for an effective tax — which in my viewpoint is a Monroe County issue, not City of Rochester. So let’s advocate for a county tax whose proceeds are directed to the arts (both organizations and individuals) in a measured way — perhaps a tax on meals, or devoting the current hotel/motel tax to the arts — something realistic….

So why is there no art funding requirement for developers who are rapidly building in this City? The City could require a 1% fee of the total construction costs to be set aside for public art. Something like this is done in many progressive cities around the world – in recognition of the important role arts play, especially in the rebuilding of downtowns. The City of Rochester could do that tomorrow. Are they afraid that creating such a fund would stop developers from developing? The City for too long has been in the undesirable position to be grateful for any crumb of new development that comes their way (be that a Dollar Store in the place of a historic building or the development of singularly ugly, utilitarian structures…another topic entirely…). So they give gigantic tax breaks and other incentives for them to build. It is time now for those developers and businesses like bars, restaurants, etc., which benefit from the presence of artists, to pay their fair share to help support them.

I also very much agree with Ray Ray Mitrano’s advice: PAY ARTISTS. When we held Greentopia Festivals, this was always the first thing we tried to make sure we did (and did do in almost every single case). Now, with the rise of downtown, is the time to start putting these things in place instead of endlessly talking about them.