On “Skalloween” weekend, Nov. 2, approximately 150 people headed to Flour City Station at East and Scio for a concert. Fitting the Halloween theme, the devilish Mephiskapheles was the headliner, preceded by Spring Heeled Jack, named for a creepy figure of legend.

Opening the night was a new Rochester band, Turkey Blaster Omega, whose lead singer wore a skeleton costume in the spirit of the Day of the Dead.

These three bands shared more than an affinity for Halloween. They all played ska.

Ska music had a resurgence in Rochester in 2019, thanks to local musicians and fans who are playing, promoting and preserving it. A concert series brought major bands to town and energized local groups who opened for them. And a ska publication created locally was featured in a new documentary film.

Local efforts highlight how through its blend of joyful sounds and social awareness, ska can lift listeners up while keeping them ethically grounded.

Members of Rochester’s ska community think its emphasis on antiracism and inclusiveness could help at this divisive time in American politics. The history of ska is multicultural, and its iconic symbol—a black-and-white checkerboard—represents interracial unity.

Small in size, with bands and audiences that are predominantly white, the local community is limited in sharing its message at this time. Can it grow in numbers and diversity to make the music’s ideals more of a reality?

A wave of ska in Rochester

Ska often is described in terms of “waves”: The first was Jamaican musicians’ development of the genre in the late 1950s and 1960s, as they combined Jamaican mento and Trinidadian calypso with American rhythm and blues. This ska developed into reggae. Upbeat and fun—ideal for dancing (or “skanking” as ska fans often call it)—it also had a depth that expressed economic hardship and the legacy of British rule. The second wave hit the UK in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as ska and reggae blended with punk music. The third made a big impact in the U.S. in the 1990s.

While ska has carried on as a subculture in the U.S. and thrived internationally, it has been out of the national spotlight since 2000. That may be changing. A story in Billboard magazine describes a rising fourth wave of ska—one anticipated for some time.

Adam Smith, organizer of the Skalloween show and four other ska concerts at Flour City Station in 2019, is bringing this momentum to Rochester. He thinks ska can lift people up and connect them.

The 2016 elections saw “so much divisiveness and hatred and awful rhetoric,” he says. He thought, “the world needs ska again. I need ska again. I need (ska bands) to come to Rochester; let’s share it here.”

Now immersed in ska, Smith only became interested in 2015. When a friend urged him to go to a show, he was reluctant.

“I’m an old-school punk, but when the whole ska thing tripped off in the late ’80s, early ’90s, and then really went crazy in the ’90s, I was all about goth,” he says. “And I didn’t want to hear something that was really happy or had a good mood to it.”

But the concert in Lewiston by the second-wave English Beat and third-wave Toasters changed all that.

“The energy absolutely blew me away,” Smith says. “I’ve gone to metal shows, punk shows, where it’s anger and rebellion and … (it’s) almost like they’re driving the angst up and out of you. And it’s powerful, it’s very therapeutic, and I still love that aspect of those shows. But this was something that felt similar but in a positive manner.”

A positive message was promoted in second-wave ska—called “2 Tone” after the record label that originated the checkerboard logo. In Britain in the late 1970s, a time of economic hardship, multiracial bands like the Specials, the Selecter, and the English Beat combined reggae and punk to create a new ska. Their music celebrated multiculturalism in working-class communities. People from West Indian and Asian immigrant communities as well as native-born families had grown up, worked, and enjoyed music together, but white nationalism threatened to divide them. 2 Tone urged solidarity in the face of hard times that have often been used to drive people apart.

Smith was inspired by 2 Tone and the alliances black Rastafarians and white punks forged in England when they were both struggling. “It’s why you see the checkerboard in ska, the black and the white put together,” he says. “And I love that message.”

Smith was eager to hear more, but traveling to shows was expensive. He decided to bring bands here.

He moved from fan to promoter after meeting Coolie Ranx, lead singer of the Pilfers, at a ska festival in 2017. Ranx encouraged Smith to find a venue for his band in Rochester, and Smith went on to organize a show at Funk ’n Waffles—the site of many ska concerts when it was the Horizontal Boogie Bar and then Water Street Music Hall. He did so well that Ranx asked him to manage the Pilfers’ national tour.

For this year’s series, Smith connected with Flour City Station, at the former Milestones (another popular club for ska) location. He booked national touring bands including the Toasters and the Pietasters, and he matched them with the four active Rochester ska bands: Some Ska Band, 5Head, Turkey Blaster Omega, and Personal Blend.

Smith, who plans to continue organizing shows in the area, says attendance hovers between 120 and 230 people. (Not groundbreaking numbers, but enough to make Flour City Station look moderately full.)

The fifth local band to play the series was the Miggedys, who held a reunion concert in August. Having formed in the 1990s when they were high school students at Pittsford Sutherland, Pittsford Mendon, and School of the Arts, they gained fast popularity locally and expanded their fan base at concerts around the Northeast. In 1995, they put out an album called “An Informal Gathering” and had a song on “Spawn of Skarmageddon,” a compilation produced by Moon Ska Records, the preeminent label for ska at that time.

A video describes how they reunited after 20 years to perform with Bim Skala Bim. Two members who live in the area—singer Tricia Gonzalez-Johnson (a teacher in the Rochester City School District) and saxophone player Nancy McKnight (an OBGYN)—reached out to bandmates around the country who were eager to make the journey.

The Miggedys’ Facebook page celebrates ska as “the only music that truly brings people of all shapes, sizes, and colors together for the greater good.” Gonzalez-Johnson says the band found the “positive upbeat” of ska was a good way to tackle difficult subjects and encourage others to listen.

Like Smith, she thinks that, in the current political situation, the world needs ska. She says its presence in a low-key way isn’t enough: a larger movement, a “fourth wave,” is needed “so everybody knows what it is, and feels it, and hears it, and applies it.”

Needing more voices

Gonzalez-Johnson recently signed on to become the new lead singer of Some Ska Band.

That group’s founder, Charles Benoit, discovered 2 Tone as a teenager in Greece. He joined the Army in 1980 and found best friends who were also ska fans. The group delved into the music and embraced the mod style associated with it: “We had scooters…, dressed in the pork-pie (hats and) outfits, and were just obsessed with listening to ska.”

Years later, while living in Kuwait, Benoit started to learn the saxophone by sitting in on an elementary-school band class, benefiting from the critiques of young classmates. Back in Rochester, he trained with jazz bandleader Dean Keller and five years ago formed a “band of misfits” who, like him, were new to performance. Some Ska Band recently released a CD (“It’s Going Down”), and they have been invited to perform at the 2020 Supernova International Ska Festival in Virginia.

Their approach is welcoming and unassuming. They invite audience members onstage to help with vocals. When Benoit expresses with pride that their CD has gotten “great reviews in the ska world,” he adds: “Keep in mind, I just said ‘the ska world.’ That’s like saying ‘the paper-cup-holder crowd.’ It’s a very small group.”

While showing humility typical of ska, Benoit stresses its scope and impact. A correspondent for the international Reggae-Steady-Ska website, he says it is “huge in Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia,” much bigger than it is in the U.S.

In songs like “End of the World,” Some Ska Band tackles issues that, affecting us at home, also extend far beyond it. Benoit admires the intriguing contrasts we hear in the best ska. Listening to the first-wave Skatalites or the Specials, for example, “you can hear the sadness coming through” and “yet it’s joyous music.”

He summarizes 2 Tone’s message as “live and work together, create together, collaborate together, and respect each other as equals.” Respect for difference is integral to the checkerboard symbol, he says: “It’s not the gray movement” or being “colorblind.” Rather, it’s recognizing that others have a different reality only they can fully comprehend. It also means remembering that ska came out of economic struggle, he says, regardless of one’s own present comfort.

Benoit thinks ska can tackle more issues, including the problem of misogyny in lyrics. He cites a recent contribution in this area by Specials fan and collaborator Saffiyah Khan. He sees ska as a welcoming forum for ideas and stresses the need for more diverse points of view. Referring to perspectives of women and African Americans, for example, he says, “We need those voices. We need those stories. We need those songs.”

Music of the people

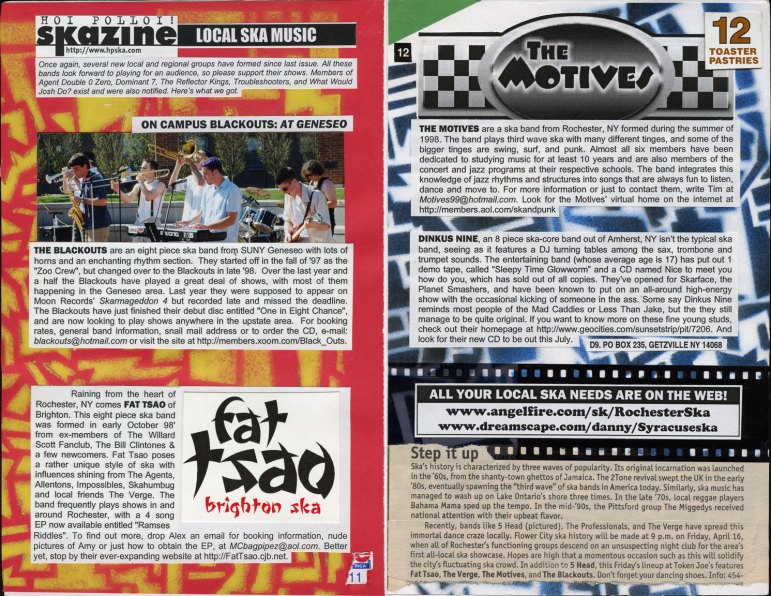

A ska magazine created locally has preserved the stories of the ska community in Rochester and beyond. Pages from this do-it-yourself publication were featured in a new documentary about the third wave called “Pick It Up: Ska in the 1990s. ”

Three Rochester teens—John Vaccaro and Dan Kress of the Maplewood neighborhood, and Eric Mearns of Pittsford—set out to create a “skazine” in the mid-1990s. They called it Hoi Polloi!, a term for the common people they saw as a good fit for the democratic values of ska.

They worked on the first issue after heading to different colleges in Western New York in 1995, meeting on weekends to cover concerts and using the 24-hour computer labs on their campuses. They printed Issue No.1 in January 1996 and soon built a reputation in the ska world, including abroad.

“The more we made them, the more the word got out. The more we wanted to make them,” Vaccaro says.

It was an ambitious project involving in-depth interviews with bands (hand-transcribed afterwards), reviews, film photographs, drawings, puzzles, and more—all painstakingly collaged on paperboard with a glue stick. Then there was the printing, sometimes done surreptitiously. “You know, ‘who’s got a job that’s got a copier?’” recalls Vaccaro. As copies were grabbed up, the friends started to incorporate publicity and letters from fans into reprints of a given issue.

It’s a local section that appears in the documentary—a collage about the Professionals, a Rochester band in which Kress played. Vaccaro says the Professionals and the Miggedys had a special appeal for his group of friends because they were around the same age. Bands like these and Hoi Polloi! itself were brought into being by teenagers who, inspired by ska, dedicated themselves to it.

Vaccaro has continued to archive ska through the Hoi Polloi! website, which includes a historical calendar, context about the zine, and selections from print issues. Among the local facts readers can discover there: Pop singer Steve Alaimo of Rochester recorded ska songs in the 1960s, Scorgies was a stop on the Specials’ U.S. tour in 1980, and the dance floor collapsed during a Mighty Mighty Bosstones concert at the Horizontal Boogie Bar in 1993.

Vaccaro misses assembling the physical publication but thinks it would be hard to take this approach in a decisively digital age.

“All the information is just so at your fingertips,” he observes. “Why would you wait six, eight, 10 months to get it in the mail?”

Skanking in upstate

One of the stories told in Hoi Polloi! revolves around the Rochester band Bahama Mama.

A reggae/rock group, they ventured into ska with the song “Upstate Skank,” which was on the B-side of their 1980 single “Lonesome Cowboy.” Ron Stackman, who co-founded Bahama Mama and later the Majestics, got into reggae around 1972. Its “mellow vibe” and the Rastafarian message of equal rights resonated with him, he says.

He and his bandmates’ interest in reggae led them “to hear where it all came from”: the original Jamaican ska. Stackman says he prefers ska of that era— which “was a little more jazzy” and “had a swing to it”—to later approaches.

“Upstate Skank,” however, sounded more like the punky ska that was just emerging. “We were loving reggae, but that was when punk was coming in, and we felt a real alliance, because reggae and punk really linked up together,” he says. And what Bahama Mama created “wasn’t the old jazzy groove, it was the up-tempo style” associated with the second wave.

This blending of styles was not uncommon. According to Chris Schepp, who hosts a ska and reggae show on WAYO 104.3 radio called Jah Crunchy’s Choice Cuts, Jamaican music heavily influenced other genres in the 1970s and early 1980s, including songs by Rochester bands New Math and the Hi-Techs.

Stackman describes the vibrant West Indian music scene in Rochester in the 1970s, including a half-dozen reggae record stores and a lot of shows.

“Things were happening,” he says. Tony Price, who owned Club West Indies on Main Street and later the Calabash, helped Stackman’s band.

“When he heard about us, we needed a place to practice,” Stackman says, “so he let us practice in his nightclub during the day, and then we’d play once in a while at night.”

Bahama Mama, whose members were white, opened for black Jamaican reggae bands such as Yellowman at Price’s.

“It helped us out a lot,” Stackman says.

On June 13, the Majestics played a rain-soaked concert at Party in the Park with the legendary Jamaican ska and reggae band Toots and the Maytals.

‘It can be better’

Rochester ska hasn’t realized the kind of multicultural scene that Price created in his clubs, or that was characteristic of the jazz-focused Pythodd Club from the 1950s to 1970s.

The 2 Tone checkerboard expresses a hope for unity. And while it shows black and white, it is clearly embraced as a symbol of diversity that reaches beyond two racial identities. Pauline Black of the Selecter describes it as “‘inclusive not only of color, but of gender.’”

Some of the national bands that toured Rochester this year reflect the multiracial membership that is important to 2 Tone. But it is evident at shows in Rochester that bands and audiences are largely white. This homogeneity calls attention to how ska’s message is an ideal, not a reality.

As Schepp puts it, 2 Tone is “an unfulfilled dream.” The “desire for racial equality … is always there,” he says. But real change remains elusive.

Schepp, who is from Irondequoit, found ska in the 2 Tone era, when he heard the Specials on the radio as a student at Sullivan County Community College. In the 1990s, he and his friend Robin Reese (who as “Dr. Awkward” hosted the Ska and Roots Emporium on WRUR 88.5 radio) DJ-ed ska shows downtown.

While looking realistically at ska’s impact, Schepp admires groups who are updating its message. He recommends UK bands the Skints (whose “Culture Vulture” is about cultural appropriation) and Sonic Boom 6 (whose “No Man, No Right” is about women’s rights).

In the 1990s, mainstream success and a proliferation of bands led some to take a formulaic approach (or even “Sell Out,” to use the title of the 1996 Reel Big Fish song). As Benoit puts it, there was a tendency to think “every song has to be fast and hard and about drinking.” The new ska appears to be shifting in a more sober direction, without losing its invigorating sound.

A rekindling of interest nationally and locally could be a positive sign, a driver of discussions about antiracism and solidarity that draw upon a rich musical history while adapting to the current moment.

Ska offers the chance to cut loose without being cut off from important issues in the community. It can help listeners find fellowship and hope. As Smith says: “You listen to the music and you look at the world around you today, and you think to yourself, ‘It can be better.’”

Esther Arnold is a Rochester Beacon contributing editor.