(Photo credit: TEDx Talk)

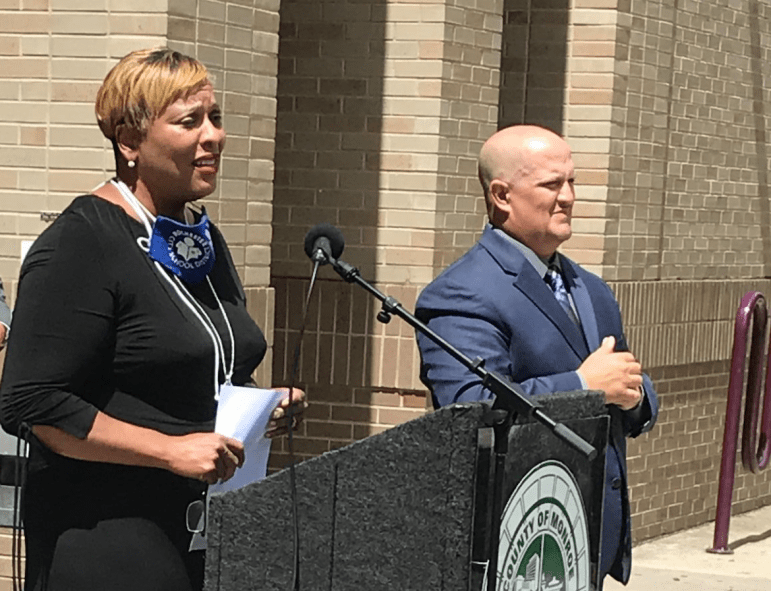

Lesli Myers-Small has landed her dream job. That some might see it as more of a nightmare does not trouble her at all.

Named superintendent of the Rochester City School District in May, Myers-Small took over only weeks after her predecessor unexpectedly quit after less than a year the job. She stepped into the position as the long-troubled school district’s ills, which had already gone from bad to worse, seemed to be rapidly deteriorating with no bottom in sight.

Greeting Myers-Small as she assumed the post was a more than $70 million budget gap. That shortfall is but one strand in a gordian knot of stubbornly persistent woes that include chronically low graduation rates and underperforming schools. These problems plague a district whose predominantly Black and Hispanic student body includes a high percentage of children whose families’ incomes hover in the neighborhood of the poverty line.

While a $35 million infusion from the state had taken off some of the immediate financial heat, it is an advance on future aid payments, a loan that eventually has to be repaid, albeit over a 30-year term.

The district’s budget woes alone would be enough to daunt any superintendent, but it is a hurdle Myers-Small must vault while also figuring out how to guide the troubled district through a pandemic.

An opportunity

Only months before she won the RCSD job, Myers-Small had begun a stint as an assistant commissioner with the state Department of Education where her duties included working with troubled Rochester schools.

When I met with Myers-Small in a September Zoom session, the first question I asked was why she chose to step out of a recently won, prestigious state-level job into a maelstrom that had spit out several superintendents before her, a job that may have no upsides.

Myers-Small doesn’t see it that way.

The question for her, she says, was not why take the job, but why not?

“Why not come to a district that had its challenges and currently has its challenges,” she says. “I actually get bored pretty easily doing the same thing over and over again. I love challenges. This is the moment I’ve been waiting for all of my life. After working 12- to 18-hour days, I go to bed tired every single night, but I love what I’m doing. This job is a joy.”

For Myers-Small, RCSD “is a district I’ve always held close to my heart. It’s where I started my career. I was an intern here when I was in grad school and then my first job in education was in the (district).”

Much has changed for the district since then, little for the better. But having landed its top job at what might be the district’s lowest point, Myers-Small betrays no doubts over her ability to handle it.

“I truly believe I have the skills, the talents and abilities that can help move the district forward,” she says.

For now, and likely for the foreseeable future, Myers-Small’s hope of moving the district forward will be circumscribed by the budget and the coronavirus.

Navigating a pandemic

Stepping into the job, Myers-Small, whose Education Department duties included serving on a team tasked with developing comprehensive information on COVID-19 for New York school districts, had a jump on dealing with the disease.

Still, she concedes, navigating the pandemic “is a complicated situation.”

“The rules of engagement have changed. Our understanding of the disease is evolving,” she explains. “You can have full-blown symptoms and it’s very clear that you have COVID; you can be asymptomatic and carrying the disease. I want to make sure that in the end I’m making the best decisions for my students, their families and my staff.”

Dealing with COVID-19, says Myers-Small, “has stretched me. I’ve had to become a Jill of all trades and a master of some. Superintendents’ wheelhouse is teaching and learning. Now, we have to be responsible for contact tracing and testing. We have to understand and know the different levels. I’ve become an expert in ventilation and air quality in schools. Trying to figure out how to maneuver through all that and to ensure that the bottom line, teaching and learning, occurs has been very complex.”

(Photo credit: RCSD)

Initially, Myers-Small planned to open city schools on a so-called hybrid basis. Students would split time between in-school classes and remote, online sessions. That plan ran afoul of the Rochester Teachers Association and restrictions imposed by the state.

Myers-Small and RTA president Adam Urbanski negotiated a deal for the first 10 weeks of school to be entirely online with hybrid learning to be revisited at the end of the period. That would put a possible hybrid reopening a few weeks away.

Since the deal was struck, Urbanski told me in late September, the union and the district were cooperating to monitor the situation and at that point had made no decision. Since then, odds of a second wave appear to be growing as local case totals tick up.

Still, Myers-Small is anxious to see children physically attend school. Academics are not her only concern. In a district with a high poverty rate, for many students, “school is their refuge.”

Doing things differently

Her spirit may be willing, but budget constraints as well as the virus itself promise to erect barriers. While COVID-19 is in the air, social distancing protocols demand smaller class sizes, which means more classes and more teachers to teach them. Would existing teaching and support staff stretch to cover? Would there be enough room in every building or might spaces have to be modified?

“One of the biggest situations for us is the transportation piece,” Myers-Small says. “The CDC guidelines, observing the six feet (of distancing), that does not solely apply to classrooms. It applies to buses, so we’re taking a look at that. It will be very difficult under the current guidelines to have children coming back full time, but we are looking at everything. We’re making sure that we do have what we need.”

A possible offset to those concerns could be the unwillingness of some families to expose their children to infection. If enough families choose not to have their children return to reopened or partly reopened schools while the virus is uncontained, social distancing challenges would be eased.

On the other hand, Myers-Small notes, the virus itself could upend the district’s best-laid plans.

“At any moment the governor can issue an executive order and say go fully remote,” she says. “That’s something that’s always in the back of my mind. I’m reading reports and hearing on the news that we could have a second wave that’s worse than what we had before. And the flu season could be particularly bad. We could have teachers who are not able to come in because they have the flu. That’s something we have to look at as well, the availability of staff.

“The goal is to eventually go back. What we’re waiting to see is the advancements as far as the vaccination, the availability of testing and rapid testing for students and for staff.”

Budget crunch

In the background are a budget shortfall and the prospect of state-aid reductions that have forced the district into layoffs that could complicate any return to in-person learning.

RCSD idled 116 paraprofessionals in August. A layoff followed this month of 200 staffers who belong to a 1,200-member union representing school sentries, clerical, food-service and maintenance workers, and other non-teaching staff.

The district’s budget crunch could ease if the state’s budget picture improves, a possibility if the Democratic Party wins the White House and control of Congress in the Nov. 3 election. As it stands now amid the pandemic, New York is facing a roughly $14 billion budget shortfall, while prospects of federal aid to help fill the gap remain dim.

If federal aid to the state does not arrive, RCSD school board member Beatriz LeBron says, the district’s budget gap would likely top $100 million.

“A lot depends on what happens Nov. 3,” concurs Wade Norwood, a Rochester-based member of the Board of Regents, the governing body that sits over the state’s Education Department.

In the meantime, Myers-Small has moved to recruit private partners to help the district maintain or install services, among them the United Way of Greater Rochester, the Urban League of Greater Rochester and the Ibero-American Action League.

“Those groups and many more are willing to support us with either in-kind or low-cost services,” Myers-Small says. “We have to be extremely open and willing to partner with different folks who are willing to help us. I have been very open to that since day one and we have lots of support.”

United Way president and CEO Jaime Saunders, whose organization helps fund services doled out by a host of area nonprofits, sees the long-trouble RCSD as now at “a watershed moment. It can’t make it on its own. It takes a village.”

Myers-Small “brings to the table the know-how, grit and heart” to pull the district through, Saunders believes, but it still faces a tough road. And while nonprofits can help ease the burden, their budgets are also stretched.

“What (Myers-Small) is facing here—COVID and so many other hurdles—will take more than the district’s resources,” Saunders says. “It will take nonprofits, families, teachers. But it’s not possible for a nonprofit to send staff without resources.”

Among initiatives Myers-Small has spearheaded so far is a grant that paid for laptops for each student and arranging for food-distribution at neighborhood centers to make up for meals Title I students used to get at schools.

LeBron also believes Myers-Small is up to the task and praises her efforts so far, but she says there are kinks still to be worked out. Students have laptops but not all have reliable broadband. Some families cannot easily make it to neighborhood centers for food pickups. A plan needs to be developed to add more pickup points.

Like Norwood, LeBron sees the budget as a sword of Damocles that could upend even the savviest superintendent’s best efforts.

Community ties

The private partners Myers-Small has been able to quickly rally point to what could be a secret weapon of sorts that past Rochester school superintendents lacked: deep local personal and professional ties to the Rochester community.

I started an interview with Norwood by asking about Myers-Small’s Education Department experience. Though Norwood is a department official, he said the question surprised him. He had expected me to ask about Myers-Small’s long and close ties to Rochester’s Black community.

“I’ve known her family for years,” says Norwood, a onetime Rochester mayoral candidate whose day job is heading the nonprofit Common Ground Health. He speaks admiringly of Myers-Small’s mother and her past local activism.

RCSD school board vice president Cynthia Elliott attends the same church as Myers-Small, the New Life Fellowship, a primarily Black church in the city’s 19th Ward.

“I knew her as a fellow parishioner before I knew her as a superintendent,” Elliott says.

Growing up in Pittsford

A Massachusetts native, Myers-Small moved to the Rochester area when she was eight after her father, a software engineer, was recruited by Xerox. The family settled in Pittsford, where it was one of only a few Black families in the upscale eastern suburb.

Despite that, Myers-Small says she fit in easily enough. She played basketball and volleyball, played the bassoon and did well in classwork. She has fond memories of high school.

“Go Vikings,” she says, “always Sutherland, never (Pittsford) Mendon (High School). We’re like the Hatfields and the McCoys.”

She keeps in touch with a circle of high school friends. While they settled the family in a mostly white, affluent suburb, Myers-Small’s parents took steps to see that she and her sister, who is five years younger, were not cut off from urban Black culture.

“Both of my parents were big activists. Knowing about my culture and my history was very important to both of them,” Myers-Small recalls. “They wanted to make sure that we were exposed to our culture and to understand where we came from. They wanted to show us about urban life, that it just wasn’t about suburban living. I had friends in the city because that was important.”

(Photo credit: Town of Pittsford)

Myers-Small and her sister also were enrolled in a local Jack and Jill of America chapter. Self-described as “dedicated to nurturing future African-American leaders by strengthening children through leadership development, volunteer service, philanthropic giving and civic duty,” Jack and Jill runs programs for children aged 2 to 19. Parents must be referred by a member to join.

In her Pittsford life, Myers-Small says, “I don’t consider myself to have been popular. But all my friends say, ‘You were incredibly popular.’ They say that because I hung out with the musicians; I hung out with the athletes. I hung out with everybody.”

Sheela Jivan, an affordable housing advocate currently working with Google on a housing project in San Jose, Calif., is one of the high school classmates Myers-Small has stayed close to.

“I’ve followed her career,” Jivan says. “I’m a real fan. I tried to get her to apply for the superintendent’s job where I live in Berkeley, but she wouldn’t do it.”

A friend since she and Myers-Small bonded as neighbors and school bus seatmates as seventh graders, Jivan describes the teenage Myers-Small much as Myers-Small describes herself, an athlete, a musician and someone who got along with and was liked by virtually everyone.

While she has pleasant memories of her teenage years, Myers-Small describes her high school as a place where, not unlike most U.S high schools, to a certain segment of the student “you were either popular you were nothing. If you were overweight or if you didn’t look like everybody else, it was a problem. I worked very hard to fight against that.”

One day as a 10th grader, Myers-Small decided to flout the unwritten code. She joined the outcasts’ table in the cafeteria. The group included a girl with a medical problem requiring her to wear diapers, a boy who had been born without arms and legs and a “very flamboyant” Black student who, although he never said as much, Myers-Small believes was gay.

“People used to throw things at them and tease them,” Myers-Small says. “When I went to sit with them, there was like an audible gasp in the room. When I sat down, they asked me: ‘Why are you coming to sit with us?’ I said: ‘Why not?’

“I used to sit with them several times a week because I thought: ‘This is stupid.’ It wasn’t because I was feeling sorry for them. I wanted to connect to individuals who were treated so poorly.”

Myers-Small sees the impulse that drove her to reach out to those classmates as stemming from innate tendencies toward empathy, sympathy and connectivity, the same tendencies that later moved her to go into school counseling.

“I was the kind of kid who always tried to settle playground soccer disputes,” says Myers-Small. She also stepped in as a mediator when her parents argued, which was something that occurred more and more often as Myers-Small entered her pre-teen years.

When she was 11, Myers-Small’s parents divorced. Her father continued to see Myers-Small and her sister, but he stopped paying household bills. Myers-Small, her sister and her mother continued to live in the newly built Pittsford home they had settled in a few years earlier. But the family went on public assistance and had to count on an area church’s food pantry to eat.

“They would give my mom a very difficult time,” Myers-Small recalls. “To get the food you had to give your ZIP code. They’d look our address and they would say: ‘You don’t need the food.’”

At her father’s insistence, her mother had never worked outside the home. When her father left, says Myers-Small, “my mom was emotionally paralyzed. She was embarrassed.”

Her mother was a junior high school dropout, a detail she hid from her children. Only as an adult did Myers-Small realize that her mother stopped helping her with homework after Myers-Small reached the seventh grade because she couldn’t do the work.

“She would say things like, ‘I could help you but this is something that’s important for you to learn.’ She didn’t have the background, but I didn’t know that. She never said I can’t help you. She just said, ‘You really need to get this,’” Myers-Small recalls.

Even so, says Myers-Small, her mother would stay up with her. She would feed her daughter milk and cookies until the homework assignments were completed, sometimes into the early hours of the morning.

Eventually, Myers-Small’s mother, who is now retired, got a GED, attended Monroe Community College and became a nurse.

For years, Myers-Small says, she nursed a deep anger toward her father. He has passed away, but Myers-Small and her father reconciled in her 20s, after he shared his life story.

He was 12 when his mother died. His father left his 12-year-old son and four younger sisters with relatives in North Carolina. He told them he would be back, but he never returned. Myers-Small’s father and his sisters ended up living in Florida. Their father remarried and started a new family.

When she and her father reconciled, says Myers-Small, “he apologized. He said, ‘I just didn’t know how to be a good dad.’”

Music is very important to her, Myers-Small told me. Her tastes are catholic, but she particularly is a fan of classical music. She rhapsodizes over a performance of Mozart’s Requiem that brought her to tears. She believes that she was literally born loving classical music.

“When I was in my mother’s womb, I was very spunky,” explains Myers-Small. “She would take a portable radio and she would put the radio on her tummy and play classical music and that would calm me right down. I loved classical music before I even made my entrance into the world.”

Landing in education

Myers-Small started taking bassoon lessons when she was eight or nine. She still plays, and though she only sits in with elementary school students, she describes her playing as good enough to play with high schoolers.

“I can sight read,” she says.

When Myers-Small was getting ready to apply to colleges as a high school senior, her bassoon teacher, who had studied the instrument at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music, strongly encouraged Myers-Small to apply there. Myers-Small demurred.

“She was so upset when I decided not to go, not to apply to Eastman,” she recalls. “I told her, ‘I love bassoon and music so much that I just don’t want my paycheck to be dependent on it. I want to enjoy it and I don’t want it to be forced.’ She said: ‘You’re African American; you play bassoon; you’re smart. You could play for any symphony in the world.’ She stopped talking to me for a little while. We worked through that, though.”

At UR, Myers-Small majored in psychology. She planned the major as pre-med course. She had her sights set on a specialty in thoracic surgery with a sideline as a medical researcher seeking a cure for sickle cell anemia.

Myers-Small’s grades for her first year and a half as an undergraduate were mediocre. For a time, they put her on probation.

“I liked to party,” she recalls. “I didn’t drink or do drugs or anything like that. I just liked to go to parties. I was getting away from my strict upbringing.”

Myers-Small decided to buckle down. She cut down on parties, hit the books and made dean’s list for her last four semesters. She graduated with a 3.95 grade point average. To celebrate, she took a trip to the Bahamas, where she had a literal come-to-Jesus moment.

The Medical Admissions Acceptance Test, a pre-condition for applying to any medical college, worried her. What if she didn’t pass? On the Bahama trip, she had taken along a copy of brain surgeon Ben Carson’s book “Gifted Hands.”

Ironically, Carson’s book, an autobiographical account of his rise as a rare Black neurosurgeon who became celebrated as the first person to successfully separate twins conjoined at the head, ended up convincing Myers-Small to give up her medical ambitions.

“I finished the book and I had tears in my eyes,” Myers-Small recalls. “I’m a person of faith, and I said: ‘Lord, I just want to do whatever it is that you have called me to do. I clearly believe that he spoke to me and said: ‘Just put the book down and look at your hands; the answer’s in your hands.’ I was like what? What?

“What I heard was: What are you good at? I went back to childhood when I would mediate the kickball fights, when I mediated disagreements between my mom and dad. I thought, I’m good at talking to people and I’m good at mediating, so what does that translate to?”

Instead of applying to medical school, Myers-Small applied for a slot in a UR Warner School of Education program that offered full scholarships to undergraduates of color who planned to pursue careers in teaching or counseling. She was rejected. The school cited poor grades at the start of her UR career. Myers-Small went to the Warner School dean to plead her case. The school reversed the decision and let her in.

Myers-Small graduated from the Warner School with a graduate degree in counseling and human development, earning the degree with a thesis titled “Afrocentric Counseling: Implications for School Counselor Practitioners.”

Myers-Small’s first job in education was as a counselor at Rochester’s School of the Arts. She though it was a neat fit with her love of music.

She later moved up to administrative posts in the district, running Wilson Magnet School’s International Baccalaureate Program and later as vice principal and school registrar for the district’s summer school program. In 2005, she moved to the Greece Central School District, where she served as director of student and career services. Two years later, she began a five-year stint as an Ithaca Central School District assistant superintendent.

In 2012, Myers-Small landed the job of superintendent of the Brockport Central School District, where she remained until moving to the state education post last January.

While some might have seen the state-level job as a launching pad to higher-level education bureaucracy positions in New York, other states or the federal government, Myers-Small had her eye on Rochester.

Myers-Small in fact sought the RCSD superintendency twice before landing it. When she applied in 2018, the RCSD board instead hired Terry Dade, a Virginia school administrator who abruptly departed with more than two years left on a three-year contract. He quit to take a job heading the Cornwall on Hudson Central School District, a public-school system in a smaller and more prosperous Orange County community 50 miles from New York City.

“When Terry Dade got the job, I told her it should have been her,” says Myers-Small’s sister, Linda Dickey. “She has a heart for this and she has the skill set.”

Dickey also is an educator. She currently chairs the Cheryl Speranza Leadership Institute at Our Lady of Mercy High School. She previously worked alongside her sister in the Rochester and Ithaca school districts.

Myers-Small’s husband, Randy Small, was not sorry to see his wife lose out to Dade.

“I was happy. The Rochester schools have some nasty problems,” Small says.

He has since reversed course. Seeing how badly his wife wanted the position, Small now says, “I was happy for her when she got it.”

Small moved from his native Chicago to join Myers-Small in Rochester. The couple first met and dated for a time when Myers-Small was a UR undergraduate. Small was visiting Rochester relatives and had arranged to meet a blind date at a UR dormitory. Myers-Small happened to be engaged in a Monopoly game at the dorm. Looking for his date, Small stepped over the game board a few times. Myers-Small playfully chided him. One thing led to another and Small never met the blind date. He and Myers-Small had lost touch for years but reconnected on social media after Small and his first wife divorced.

Dealing with the board

That Myers-Small did not make the board’s final cut in 2018 mystified LeBron.

“She would have been my choice,” LeBron says. “I really don’t know why she was eliminated.”

In the final round of the district’s 2018 superintendent search, the man Myers-Small replaced, Dade, and two other out-of-town candidates had vied for the position.

Dade, who lasted 10 months on the job, had hinted that tensions between the board, a body with a long history of testy dealings with superintendents, played a role in his abrupt departure.

LeBron doubts that.

“I’m no fan of the board myself and I’m a member,” she says, conceding that the body at times has bedeviled past superintendents. “But I didn’t see that with Terry. He’d never run an entire school district before, let alone one as large as Rochester and with these kinds of problems. I think he realized he just wasn’t up to the job.”

Tensions with the school board have played a role in driving several RCSD superintendents from the district. Dade’s predecessor, Barbara Deane-Williams, bowed out early, leaving a worsening budget behind. Shortly before she announced her early departure, RCSD school board president Van White said of Deane-Williams’ tenure: “It’s just not working.”

White, who did not respond to a request for comment for this article, had been president when Deane-Williams’ predecessor, Bolgen Vargas, quit early after the board insisted on a right to hire and fire member of Vargas’ cabinet.

The RCSD board’s penchant for meddling in district affairs that should more rightly come under a superintendent’s purview later came under fire in a 2018 report from Distinguished Educator Jaime Aquino, an official appointed by the state to assess the district’s academic shortfalls. After RCSD budget woes deepened, the state appointed a monitor, Shelley Jallow, to work with the district to improve its finances and academic results.

Her recent stint as an Education Department assistant commissioner, says Myers-Small, “only helps the Rochester City School District. The commissioner (Betty Rosa), who used to be the chancellor, and I have a phenomenal relationship. If there are things we need, if we need assistance, technical boots on the ground, we are getting that right now through a couple of offices.”

Myers-Small is very well thought of in Albany, Norwood affirms. Her State Ed connections are “a huge advantage.” Rosa and other top department officials “have a strong desire to see (Myers-Small) succeed,” he says.

Myers-Small says her relations with the RCSD school board are good. She sees no reason that they won’t stay that way. If there are differences of opinion, she says, citing her experience in mediation as a counselor, “we’ll have a dialogue; we’ll have a back and forth. I enjoy the back and forth. I think discussion is healthy.

“They need to question; they need to push and they need to challenge me,” she adds. “I should be prepared to be able to do that. This is the third largest school district in the state of New York. We’ve got over 25,000 children we’re responsible for. If after I’ve presented the information, if that’s not the direction they want to go in, then I have to accept that. I’m not going to pout. We’ll move forward.”

As does her fellow board member LeBron, board vice president Elliott speaks admiringly of Myers-Small, whom she hopes to see stay in the job and succeed where past superintendents have stumbled.

“(Myers-Small) is committed and she’s not going anywhere,” Elliott says.

Still, like LeBron, Elliott also concedes that the district faces a far worse concentration of woes than it has previously confronted.

The RTA’s Urbanski, who over some four decades has seen a dozen superintendents come and go, says Myers-Small’s relations with the board have indeed been very good so far, “but there’s always a honeymoon period.”

Focusing on new strategies

For now, Myers-Small awaits a time when the Rochester school district won’t be hemmed in by a soaring budget shortfall and a pandemic. While the schools are shuttered, she is visiting buildings, planning for the day students will return. When it does, she hopes to shake things up.

Myers-Small does not see a district whose operations have been upended by the pandemic as merely resuming its previous track when it reopens or fighting just to stay even before until that happens. She has bigger ideas.

As an example of the type of innovation she would like to try, she mentions a proposal she floated to top Education Department officials last spring shortly before the virus hit.

“I proposed to then Chancellor Rosa and two of the regents, I said: ‘We’re so focused on attendance, we’re so focused on brick and mortar; but I can tell you, and I knew this from visits to Rochester, that’s where I got it from, that there are students who are doing e-learning, who are getting stellar grades, who are just not attending between 8 a.m. and 3 in the afternoon. They’re logging on at 7, 8, 9, 10 o’clock at night and they still are successful. So, could there be a modification or an amendment to the regulations that allow schools to have some flexibility if they can show students are participating in school from 7 to 9 p.m. Monday, Wednesday and Friday, why can’t that count as attendance?’”

If that idea were implemented as a statewide regulation or as a waiver or pilot project for Rochester, it would raise the district’s academic scores and, because state funding is linked to attendance, it would also bring in new revenue. Might it happen?

“The chancellor and the regents said they would be interested in taking a look at that,” Myers-Small says.

She wants to set up brainstorming sessions like Google’s innovation day for RCSD staff. In Google’s innovation day sessions, participants “take money out of the equation, take rules, regulations policies out and just say here are things we want to try new in our organization.”

“I would really like to start thinking about ways to do that here. I was just on the verge of doing that when I was in Brockport,” Myers-Small says. “We keep on looking at the challenges that COVID-19 presents. We also have to look at the opportunities. Just in general, we have to look at what opportunities are available in Rochester and how can we do this differently.

“Instead of saying I want to look outside the box, let’s blow the box up. Let’s just try to completely reinvent something.”

Will Astor is Rochester Beacon senior writer.

I found the article on Ms. Myers-Small to be not only very informative, but very revealing about her attitude toward the challenges that lie before her & the RCSD community, particularly its students. This, despite Mr. Eagle’s lengthy and sometimes contentious arguments about her.

I only hope that she is successful in doing what others have failed to do and will render support as best I can, as I hope everyone in the local community will do.

Thank you for this excellent piece of journalism.

Mr. Gaudioso,

I don’t see what’s so-called “contentious” about the FACT that, like all RCSD superintendents before her (with the ONLY exception being a white woman — Barbara Deane-Williams) — Ms. Myers-Small is clearly reluctant to deal with the RCSD’s BIGGEST problem, e.g., the herd of elephants in the living room:

* https://www.democratandchronicle.com/story/local/communities/time-to-educate/stories/2018/07/13/racism-rcsd-rochester-city-school-district-howard-eagle-investigation/760499002/

* https://www.democratandchronicle.com/story/local/communities/time-to-educate/stories/2018/08/02/rochester-school-district-faces-years-anti-racism-training-overcome-structural-racism/795424002/

* http://southwesttribune.com/news/working-rid-institutional-structural-racism-rochester-city-school-district/

Wow! Thank you Will Astor for enlightening us on the real Rochester Superintendent.

It sounds like she is a superintendent with: super – intentions!

FYI

Dr. Myers-Small wrote a short book of advice called “LIFE’S LEADSHIP LESSON”

https://www.amazon.com/Lifes-Leadership-Lessons-Lesli-Myers/dp/1983780308

I like her intention to REINVENT.

However, I fear that others in the RCSD system will likely resist new ideas for change.

Do we have PRINCIPALS, with great PRINCIPLES? Do we have teachers, not CHEATERS?

(TEACHER and CHEATER contain the same letters)

I, myself, have a few ideas, which have met with rejection from people on the RCSB.

1) I suggest the use of simple devices to motivate students, such as the EASY button.

2) I suggest the use of short motivational YouTube videos, such ALTERNATIVE MATH

( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zh3Yz3PiXZw ) ALT MATH 8 minute spoof

3) I suggest RCSD welcome any and all suggests and outside help through some CHANNEL

I hope this crisis will create a new sense of URGENCY for learning with SUPER INTENTIONS!

Harry S. Pearle, Ph.D. http://www.SavingSchools.org

Why is it that we are the only district without in person classes? Every other district has at least some form of in person at this point. Heck, even NYC has opened. Why is it all white kids get to go to school and none of our black community?

I’m not sure if your question is rhetorical or not, but if you seriously do not know the answer, it can be found in the two articles at the links below:

http://minorityreporter.net/the-tripartite-beast-and-illness-of-individual-institutional-and-structural-racism/

http://minorityreporter.net/the-ongoing-struggle-for-educational-equity-an-open-letter-to-the-local-black-community/

The Commissioner’s loss is Rochester’s gain. I work in educational communications and I have attended a few of Lesli’s seminars at conferences. She is amazing. She’s an excellent communicator, well-organized and engaging. She will face Rochester’s problems directly and won’t avoid the district’s stakeholders’ questions and concerns. Everyone will know where she stands on the issues, what her plans are, and how they can help the district succeed. Education is a team sport people!

You can attempt to present Ms. Myers-Small as a super-sheroe-type, but I guarantee you — she is NOT.

It is interesting (to say the very least) that “When [you] met with Myers-Small in a September Zoom session, the first question [you] asked was why she chose to step out of a recently won, prestigious state-level job into a maelstrom that had spit out several [scores of] superintendents before her, a job that may have no upsides.” If you were truly interested in a fully honest answer, all you would need to do is check her salary and benefits at her previous, “recently won, prestigious state-level job,” and compare that to the present. I gua-ran-damn-tee you that you will easily discover a BIG part of the answer that you claim to be looking for.

If your unusually-lengthy treatise is meant to be exploratory and revealing in nature, it’s a little strange that apparently you, and/or your editor chose NOT to press for clarity regarding certain, critical questions. For example, what in the heck does it mean that: “In a district with a high poverty rate, for many students, “school is their refuge” ” WHAT??? School is NOT a so-called “refuge”. Instead it is supposedly an institution designed strictly for teaching and learning (that’s all) — period. “Refuge” — what??? How??? Another such super-hyper, rhetorical assertion is as follows: “We’re making sure that we do have what we need.” WHAT??? What in the heck is that supposed to mean? WE OBVIOUSLY DO NOT “HAVE [EVEN NEARLY] WHAT WE NEED.” This is NOT a time for super-hyper; super-liberal rhetoric (not while we’re clearly moving toward third-world educational conditions). Children’s, but NOT hers, lives are literally on the line. Thirdly, “…Myers-Small’s long and close ties to Rochester’s Black community ???” You mean her “long and close ties to [a SECTOR of] Rochester’s Black community,” and definitely NOT the sector that comprises the overwhelming majority of RCSD students and families, and/or the sector that’s suffering the most. Her ascendancy, like that of so many other local blacks who clearly exhibit negropean ( https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Negropean ) tendencies, represents an exemplary sample of the reality discussed in the article at the following link: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/07/education/edlife/black-america-and-the-class-divide.html , which has clearly worsened since 2016.

“While the schools are shuttered, she is visiting buildings, planning for the day students will return. When it does, she hopes to shake things up.” WHAT??? She will NOT “shake [anything] up” — NOT significantly, nor fundamentally, as long as she is not willing to confront (head-on) another pandemic (see associated comments — https://www.facebook.com/RCSDNYS/videos/3538408622889704 ),which preceded covid by decades and centuries, and which she appears (like so many others before her) — to be running away from — because she’s afraid of the BIG, BAD, WHITE-SUPREMACIST-BASED-BOGEY-MAN : https://rochesterbeacon.com/2018/11/01/is-he-the-real-rcsd-superintendent/ — period.