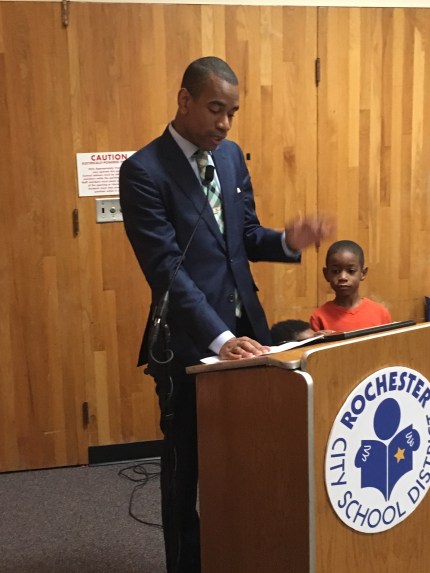

(Photos provided by Malik Evans)

If Rochester voters are expecting a heated, relentless exchange of barbs during the Democratic mayoral primary, they’re not going to get it.

City Council member Malik Evans, who threw his name into the ring last month as Mayor Lovely Warren seeks a third term, says he will not engage in that type of fight.

“I stay focused on my mission,” says Evans, when asked about a statement from Warren’s political action committee upon his entry into mayoral race. “It takes too much time and energy to focus on the tit and tat, and back and forth of politics.

“It knocks you off your mission. Then the time you spend responding to people’s comments are less times that I am spending talking to a voter or talking to someone about what I can do to help, assist them in making their life better.”

On Jan. 18, Friends of Lovely Warren stated that her campaign was prepared for the moment when a male would enter the race.

“All over the country unfortunately it’s been our brothers that have been first in line to take on sisters. The powers that be playbook hasn’t changed since the days of slavery. We know our ancestors are looking down upon us and asking … when will our people learn,” the statement reads.

Evans’ cool and collected approach is emblematic of how he lives his life and serves the community. A financial wellness manager at ESL Federal Credit Union, Evans has served terms on the Rochester City School Board and on City Council. Most notably, he is known for being the youngest person to be elected to the school board, at 23.

Now 41, Evans decided to run for mayor in an effort to solve Rochester’s challenges—from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and unemployment to social unrest over policing—and to bring a divided community together.

Having Warren as an opponent did not influence Evans’ decision.

“I think that if you have something to say and something to give it should not be dependent upon the person,” Evans says. “I’ve always said I’m running for an office and not against someone and that’s going to be my focus in this campaign.”

He adds: “It has to go beyond a cult of personality and more so what you’re going to do to advance the city and everybody feels that their voices are heard.”

Raised to serve

Listening to others and serving was a tenet of Evans’ childhood. Born to Gwendolyn and Lawrance Lee Evans Sr. at Highland Hospital, Evans’ capacity to learn was put to the test early on.

In elementary school he was one of the first students to participate in a program that had English native speakers and Spanish speakers. Evans learned math, social studies and science in Spanish.

“My parents knew that we lived in a global society and that it was important for their children to be exposed to all different types of things and people,” he says. “When I was in kindergarten I said, ‘No, I don’t want to go into this program … it’s going to be hard to know the language, things are going to be different.’ (My parents) insisted upon it and they said, ‘In life you’ll have to get to know different people, you’ll have to bridge gaps with different people.’”

Learning about culture and history, African-American history in particular, was an essential part of growing up, as was yoga and meditation.

“They wanted me to know that I came from descendants of people who did great things, and that you have an obligation to give back,” Evans says.

Lawrance Evans came to Rochester in 1970, upon his enrollment at Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School for a graduate degree. Driven by a passion for education and uplifting others, he worked with various community organizations, including Action for Better Community and Rochester Mental Health. As a minister, he ran a small nonprofit called First Community Interfaith Institute, now operated by Malik Evans’ uncle and sister, which aimed to offer community-based solutions to problems.

While Lawrance Evans’ faith was Christianity, he embraced all religions. He also tutored neighborhood children and older adults who never learned to read. Evans’ mother did different things over the course of her life—she was a librarian, ran a day care, and was a partner to her husband in his community work. Gwendolyn Evans died in 2012. Lawrance Evans passed away in 2018.

“My father did his undergrad in business administration but turned down a job on Wall Street,” Evans says. “I always joke and say he took a vow of poverty to help the community. That was his mission and that’s what he instilled in us.”

People who had fallen on hard times were often guests in the Evans home.

“My parents would always have a room for them,” Evans recalls. “We always had this sense of purpose and belief.”

Jim Kraus, a retired English teacher, recalls when Evans walked into his 10th grade English honors class at Wilson Magnet High School.

“No one listened harder than Malik; with a smile on his face and eagerness to learn, he was all ears,” he says. “He was all attentive all the time. He was attentive if another student was speaking (and) he was attentive if you were speaking.”

Getting involved

Evans’ dedication to service became apparent at Wilson Magnet High School. He won the Martin Luther King Jr. Citizenship Award given by the Rochester Teachers Association for three consecutive years. The award is given to a student, based on nominations across the Rochester City School District, whose behavior, actions and demeanor most epitomized King, Kraus says.

“You might figure in some schools someone would say, ‘We gave that to Malik last year, let’s give this to Joan or Harry or Peter this year,’” Kraus says. “His actions so characterized what they were looking for that they gave it to him again and again and again.”

An involved student, Evans was instrumental in founding the Rochester Teen Court, a program where teen jurors recommend sentencing, and serve as attorneys and court personnel for their peers who committed minor offenses. He tutored students as well, like his father did.

“This capacity to help, to reach out, to do something extra I think was imbued in him by his parents and they had a ready recipient in the young man who was Malik,” Kraus says.

Evans also started the City County Youth Council, now called Youth Voice, One Vision, a group of people who represent Rochester’s youth, and he got young people involved in philanthropy through the Youth As Resources program.

“The board consisted of adults and young people learning from each other to support service projects that kids were doing through grants that they would deal with under the tutelage of an adult to solve a community problem,” Evans says.

He kept his contributions going while attending the University of Rochester on and off campus. Evans was treasurer of the Students Association, chaired the Students Appropriation Committee and helped launch UR’s College Diversity Roundtable.

A year after graduation, Evans ran for a seat on the city school board and won. He was chosen to be president of the board for three terms.

“My biggest claim to fame that I say I want on my tombstone is the expansion of universal pre-kindergarten,” Evans says. “That was important to me. Securing initial legislation for the facilities modernization project was big for me and also ensuring that our schools had nursing services when that was cut.”

On Evans’ first school board campaign, Kraus, who has a deep abiding interest in politics, signed up to help. Kraus, a former committeeman in the city’s 27th legislative district, has carried petitions for many Rochester political candidates like Joseph Morelle, Susan John and the late Rochester Mayor Thomas Ryan Jr.

Kraus, who is a campaign adviser for Evans’ current race and serves as assistant campaign manager, says he signed on again because he believes Evans would bring strengths to the management of city government.

Evans began his professional career with M&T Bank. He left M&T as vice president and joined ESL, where he manages the credit union’s financial wellness service line. His work in financial services has focused on financial education. Economic empowerment is extremely important, he says. Evans continues his community work through board memberships. He has been a board member of the Rochester Area Community Foundation, PathStone and several other organizations.

His upbringing and community involvement have kept Evans in close touch with city residents and their needs. Evans maintains a sharp focus on doing the work at hand, a lesson he says he learned from his parents.

“They said if you were in the limelight too much, people might stop focusing on the work that you’re doing and your head would get too big,” Evans says. “I’ve kind of lived by that mantra. I’ve never been good at beating my chest because my parents weren’t good at it.”

A community compact

Nonetheless, Evans is ready to take on the public challenge of building trust and being transparent with the community. It forms the basis of his mayoral campaign, which promises to “build bridges.”

Evans wants Rochester to thrive, while ensuring every Rochester resident can earn a livable wage. Tapping the area’s bright minds in the public and private sectors and channeling its entrepreneurial spirit to create jobs and showcase innovation are some of Evans’ ideas to grow employment.

“Survival is fine. Cities survive, but the question is, (is) that city thriving?” he says. “I want to make sure Rochester thrives. There is no reason why Rochester should not be a tech hub, an innovation hub. We have the brain power in this region to be the Silicon Valley of Upstate New York.”

Evans points to Rochester Institute of Technology’s Center for Urban Entrepreneurship, where he served on the board, as an example of the resources available in the community. He also is a founding member of the Commissary, downtown Rochester’s kitchen incubator, which is geared to offer food entrepreneurs access to commercial-grade kitchens to further their businesses.

“We have some of the smartest people and some of the best resources around, but you got to bridge the gap from that person on Joseph Avenue to that person that might be at that tech company,” he says.

Stable neighborhoods where citizens are empowered to voice their opinion to influence growth and development where they live and feel safe are other elements of Evans’ vision.

“It is important for people to feel safe in the city, but on the other end also for people to feel that they can trust the community,” he says. “We know that we have large communities of color that have absolutely no trust for the police and they would rather deal with the issue themselves than call the police department.”

Like many in Rochester, Daniel Prude’s death hurt Evans. He dealt with the incident personally as a Black man who had his own challenges with law enforcement, including being mistaken for a drug dealer, and as an elected official who learned about the tragedy months after it occurred. He decided to find out as much as he could and be constructive about making sure it wouldn’t happen again. Evans was one of the City Council members present during former Rochester Police Chief La’Ron Singletary’s deposition.

“I got to see how I am going to structure these conversations with my sons because I thought they wouldn’t have to deal with this, as young boys,” Evans says.

Restoring trust and holding city government accountable, with access to data and information, is an essential component of Evans’ plans, details of which will be rolled out as the campaign progresses. If elected, he would like to not only surround himself with people who operate in a trustworthy manner and are able to connect with every sector of the city, but also be truthful about what’s happening on the ground.

“After you have this reconciliation where you’re willing to admit the things that will go wrong, you then have to get everyone in the room to say, ‘Here is where we are, what steps can we take to solve this?” Evans says. “You also have to get people to also agree and understand that there’s going to be these tough arguments, but a leader is going to have to be sensitive enough to know that it’s OK for people to disagree with you and (that) it’s not them going after you as a person but they’re talking about the office that you’re holding. So, you have obligation to try and create that environment where you can solve these challenges.”

Evans says what sets him apart is his ability to talk to people from different walks of life, a track record of listening and bringing people together to solve problems, and leading with trust and transparency. It is the message he hopes to take to people who may not know him as well as others.

Challenging an incumbent

In a video announcing her decision to seek another term, Warren speaks of her administration’s accomplishments related to jobs, infrastructure, neighborhoods and public safety. She promises to ensure equal opportunity for everyone, so that a “ZIP code isn’t your destiny and where you start isn’t where you have to finish.”

The last time she was challenged as an incumbent in the Democratic mayoral primary, Warren defeated former RPD chief James Sheppard and former journalist Rachel Barnhart, now a county legislator, winning 62 percent of the vote.

This time could be different. Dave Garretson, former chair of the Monroe County Democratic Committee acknowledges Warren’s effectiveness as a candidate and the power of incumbency, but he also believes Evans has a chance to win the race.

“The mayor is an excellent campaigner,” he says. “So, he has his work cut out for him. However, he’s not coming without pluses. For one thing he’s been in citywide elections three or four times and done very well every time he’s been on the ballot, usually coming close to the same number of votes that the mayor got in her races.”

Garretson also notes that the mayor has demands on her time and money, with a looming court case that alleges Warren violated campaign finance rules and committed fraud in her 2017 run for office.

“A huge number of people are loyally supportive of (Warren), but not everybody, and there’s a crack and he might be able to work that to his advantage,” Garretson says.

Evans did not go through the MCDC’s designation process before announcing his plans. Last weekend, the committee concluded a 75-day process to fill the more than 150 local positions across Monroe County. More than 1,800 elected Democratic committee members had a chance to vote for endorsed candidates. Warren got 62.5 percent of the vote.

The Democratic party in Monroe County has been fraught with division—split between those who align Warren, those who are Morelle loyalists and still others who choose not to align with either camp.

“I didn’t go through that (designation) process because I wanted to be able to stay above the fray and build bridges and not get bogged down into internal party division which has nothing to do with the person who’s trying to find a job on the east side of the city or nothing to do with the person who is trying to recover from COVID,” Evans says. “They don’t care about any of that. They don’t care about party politics, they don’t care about previous slights and they don’t care about ego.”

His neutrality “drives people crazy,” Evans observes.

“I don’t fall into camps. Never have, never will,” he asserts. “That’s the essence of having a father like minister Lawrance Lee Evans Sr. He was the same way. That’s the way we were raised. We don’t do camps. We don’t fall into camps because the camp we fall into is the community camp.”

Spreading the word

While he understands that politics is important, Evans notes that the arena has become divisive and corrosive, resulting in disenchantment.

“Politics, if it gets in the way of progress, it has to take a backseat,” he says, adding that he would have zero tolerance for corrosive politics in the business of governing.

The Evans team has a mix of people who are interested in change and newer to politics. It includes family and friends and others who are keen to see a better Rochester.

Once the news spread that Evans was running for mayor, Kraus says, teachers texted him to ask how they could help. The volunteer corps is growing, he says.

While Evans declines to disclose his plans for financing his campaign, he acknowledges that dollars are a factor, and that campaigning could be tough under the cloud of COVID. His campaign will raise enough money to be competitive and will have to learn to be innovative with reaching voters, he says.

“One of the biggest challenges is putting a message out in a COVID environment when a message like this is best delivered face to face with multiple people,” says Evans, who prides himself on his street work and talking with people. “So, you have to figure out how do you make up for that when you’re looking at a universe of voters and you’re dealing with the worst public health crisis in 102 years.”

Garretson says Evans will need to fill his campaign coffers, but doesn’t view it as an unachievable task.

“Malik is in the business community, he’s been in elected office a long time,” Garretson says. “A lot of people will come to support him simply because they don’t want to support her. So, money is going to show up for him. (Warren has) got demands on her money, she’s got to defend herself in court and I think that’s probably coming out of her campaign funds.”

The state Board of Elections campaign finance database shows Friends of Lovely Warren with a current balance of nearly $122,000.

While Evans just has to win for himself, Garretson says, Warren will need to make sure she carries herself and allies she wants elected on City Council and the school board. The mayor has a lot of persuading and convincing to do, he adds, which will tend to even the race out.

Says Kraus: “We think the leadership and the ethics and the positive reputation that he’s earned in Rochester will enable him to compete in what will be … a very tough race. This is not a race where one person or the other will go out and get 60 percent of the vote. That’s not going to happen.”

Evans has 42 days to gather and file petitions and 132 days to persuade Democratic voters that his leadership is the best choice for Rochester.

Smriti Jacob is Rochester Beacon managing editor.

Unlike a few of these commenters I don’t actually know Councilman Evans personally but I’ve heard him speak numerous times at City Council meetings and I’ve been continually impressed with his steadfast focus on doing the work and finding the right solutions to problems. I think he’s a realist and a pragmatic thinker and that is the best kind of leader a city can hope for. I cannot wait to vote for Councilman Evans in the primary!

Malik….wish I lived in Rochester so I could vote for you! Best wishes always to a well deserving old friend. Linda Goodwin U/R

I’m inclined to vote for Mr. Evans for Mayor. Reason number one is, he is not Lovely Warren. She’s had two terms and I don’t see much positive change as a result of her holding the office. I don’t know much about Mr. Evans, but maybe it’s time to embrace a less controversial Mayor. One thing that no candidate ever does, but I’ve always believed would help voters decide would be for them to tell voters who they will pick for top spots in their administrations. If they don’t want to name names, at least tell voters what the key attributes they would be looking for. I understand that many elected officials like to appoint people who worked on their campaigns, which is fine as long as they are qualified. Mayor Warren has staunch support because of who she is, rather than what she’s done. Change would be good.

I have known Malik Evans for over twenty years.

I have watched him lead as a RCSD Board President and City Council member.

I have watched him work with teenagers.

He understands urban leadership from experience and scholarship.

His spirit as a leader is inspirational.

He is everything we need in our next Mayor.

Friends of Lovely Warren are essentially saying that no man has the right to challenge a woman incumbent. To be blunt, that’s sexist. Any citizen has the right to run for mayor, and the Friends should be ashamed of themselves for making an ad hominem attack rather than engaging any opponents on the merits.