Jacque Woods, 34, stood on the sidewalk in front of a vacant, weed-strewn lot at the corner of Aab and Chace streets on Rochester’s west side, about a half mile north of Lyell Avenue. It’s a neighborhood of modest, mostly one-story homes. School No. 54 stands next door. It was a quiet mid-afternoon on a weekday in August.

“I’ve never done this before,” Woods told me, “but I would love to be able to walk in there.” And then with strength gained through years in the Army National Guard, she pushed aside a 6-foot-tall wire mesh fence and stepped into the physical space that 30 years earlier had been her family’s home—the site both of a tragedy and an heroic act. Both changed her life forever.

Burn scars were visible on the outside of Jacque’s right forearm; on the inside was a tattoo. In fancy script it read, “The pain passes, but the beauty remains.” Later, she told me, “It’s my life quote. It’s about growth through pain.”

Have you been back here since the night of the fire?” I asked as we stepped over weeds and wildflowers.

“I have not,” she said, her eyes beginning to tear. “I’m a little overwhelmed.”

A search for heroes

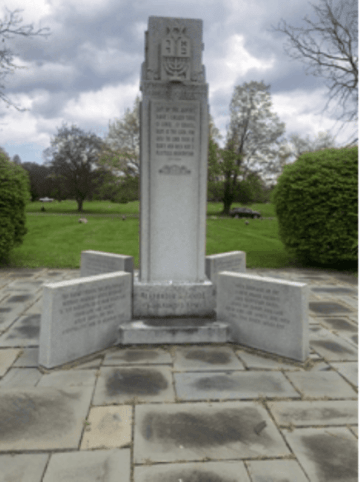

My interest in heroism started this past Memorial Day when I visited White Haven Cemetery in Pittsford and wrote about a monument there honoring the Four Chaplains. To recap: During World War II, when the troop carrier on which they were sailing in the North Atlantic was hit by a Nazi torpedo, four U.S. Army Chaplains of different faiths—a priest, a rabbi, and two Protestant ministers—helped distribute life vests to the men onboard, and when those ran out, each gave his own life vest to a soldier who had none, and together they went down with the ship. For their sacrifice, the chaplains posthumously received a congressional medal, a postage stamp was issued in their honor, and they were memorialized in dozens of monuments in cities and towns across the country. They were true national heroes.

All of which got me wondering: Are we still able to have national heroes in this country? Or have we become so divided by politics and ideology that it would be impossible for us all to agree on who is a hero? As a society, what would we lose by not having heroes?

Photo by Elisa Siegel

To be sure, we’ve had other heroes since the Four Chaplains: early astronauts Alan Shepherd and John Glenn, come to mind. So does Martin Luther King Jr. First responders on 9/11 and passengers who fought back on Flight 93 were heroes, too.

But it’s been a long time—nearly a full generation—since we’ve been able to add national heroes even to that short list. And today our divisions grow ever deeper. The news media compete to uncover flaws in even the most accomplished among us. Social media dissects everyone’s past, even back to high school, to find something to offend half the country—or at least a vocal minority—and to “cancel” an elected leader, beloved entertainer, or historical figure.

But what if we could find national heroes today? Who would those people be, what might they have done, and how would they withstand the intense scrutiny? Are such people out there but just overlooked?

Heroes “elevate us emotionally,” explains Scott T. Allison, professor of psychology at the University of Richmond. “They heal our psychological ills; they build connections between people; they encourage us to transform ourselves for the better; and they call us to become heroes and help others.” In other words, heroes make more heroes. For individuals, notes Peter H. Gibbon, in his book “A Call to Heroism,” heroes “teach us to push beyond ourselves and our neighborhoods in search of models of excellence. They enlarge our imagination, teach us to think big, and expand our sense of the possible.”

I decided to begin a search for today’s heroes—what I’ve come to think of as a “Fifth Chaplain”—and chose to begin where I’d first learned of the Four Chaplains, here in Rochester.

Honoring heroes with beer

“Heroes don’t look like they used to … they look like you do.” I found this slogan on the website of Heroes Brewing Co., a local craft brewery. Whoever came up with this, I thought, is someone I should talk to—maybe they know something about heroism in America today.

Heroes Brewing sits in a tiny, eastside strip mall near the intersection of Atlantic Avenue and Culver Road. Greg and Marlene Fagen founded Heroes in 2016. Greg Fagen keeps his day job as a program manager at Hewlett-Packard, but with five employees the brewery runs full-time and generally sells as much beer as it can produce. On a summer morning, Fagen gave me a tour of the production area: eight steel fermentation tanks and stacks of burlap bags full of oats, wheat, and barley. To show me what the barley looks like, he easily ripped open a 55 lb. bag—at 50, Fagen remains stocky and strong; in high school, he lettered in lacrosse.

Out front near the bar, we sat at a high-top table and talked about the brewery business, and about heroes.

“Why heroes?” I asked Fagen. “It’s an unusual theme for a beer.”

When Marlene and he decided to open the business, he explained, they needed a name. “We were sitting at the dinner table just noodling over possibilities. First, we were going to name it after our dogs, but then I asked Marlene, ‘What is it that anyone can be?’ She looked at me, and then I said, ‘Anyone can be a hero.’ It just came like that out of the blue.”

“And the slogan?” I asked. “‘Heroes don’t look like they used to … they look like you do’—what does that actually mean?”

The phrase comes from the song, “Nothing More,” he said, by the band, Alternate Routes. He heard it on TV during the closing ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics.

“The song perfectly stated what we wanted as our message: that the hero isn’t the guy with the cape or the uniform, it’s the guy who you have no idea what’s going on in his life, who’s toiling every day and no one’s giving them a thank you. They look like all of us—everyone can be a hero.”

But does that become like a participation trophy? I asked.

“I know what you mean,” he said. “The notion of hero has been bastardized, especially during the pandemic. Every TV commercial was: ‘Be the barbeque hero. Buy this grill!’ But we want to shine a light on real heroes—ordinary people doing extraordinary things—and those lump-in-the-throat moments when you see somebody do something that restores your faith in humanity: like the mom or dad working two jobs but at night still finds time to read to their kids, or the woman who buys books for all the children in her neighborhood.”

The Fagens’ well-intentioned idea to honor individual local heroes, however, didn’t worked out as planned.

“Turns out those people are hard to find,” said Greg Fagen, “and you never know all there is to know about someone.”

Intense scrutiny of anyone who becomes a public figure was a factor.

“The media—and especially social media—tears everyone down,” he said. “They find the skeletons in every closet. They’ll critique and chop away at somebody until there’s nothing left of them.”

So, instead of honoring individual heroes, Heroes Brewing shifted to honoring local nonprofits. Every month they partner with a different charity, avoiding issues that might be divisive, like religion and politics. “Beer is a social beverage,” explains Fagen. “We’re trying to bring people together, not further divide them.”

A chalk board near the bar listed charities the brewery was then honoring: Advent House, a hospice (beer: Cookie’s West Coast IPA); Rock Star Academy, a music scholarship fund (beer: Spin-a-Colada); and One Soldier at a Time, a group supporting families of soldiers and veterans (beer: Oscar Sierra Tango).

Even so, Fagen anticipates eventual “blowback,” when leaders of charities he’s honored turn out to have skeletons of their own.

“I’m sure all of them are perfectly imperfect, too,” he says. “So, eventually we’ll get a punch in the face when it’s found the leader of one of these was embezzling, or molesting kids, or running drugs. It’s inevitable.”

My visit to Heroes Brewery left me both uplifted—the Fagens are doing a public service while making great beer—but also concerned. They had originally planned to honor individual heroes but had given up; on a local scale, they had run into the same problem plaguing the country: Individual heroes are hard to find, especially those who would be broadly accepted.

Carnegie Heroes

Soon after my visit to the brewery, however, I discovered a venerable resource for finding local heroes. In 1904, I learned, industrialist Andrew Carnegie created the Carnegie Hero Fund to honor local people who risked their lives to save others. Winners would receive a gold medal and a cash award.

To date, the Carnegie Hero Fund has recognized more than 10,000 heroes, 22 of them from Rochester. Recent winners are Jason A. Sigelow, 39, of Irondequoit, who in 2017 lost his life while trying to save a 9-year-old boy from drowning in Lake Ontario; and Christopher Patino, a high school student, who in 2011 rescued a teenage girl who’d been attacked by a man with a knife at a grocery store in Henrietta.

I wanted to talk with a Carnegie Hero whose deed had occurred recently enough so they were still living, but long enough ago so that they’d had the better part of a lifetime to reflect on its meaning and on the notion of heroism itself.

Sixty seconds in a burning home

Kurt Ernst, 63, is retired and lives with his wife, Jeanne, in East Aurora, near Buffalo. But the event for which Ernst received a Carnegie Hero Medal occurred in Rochester on Dec. 2, 1989. He was 31 and worked as a meter reader for RG&E.

“I just fished my Carnegie Medal out of my sock drawer,” he told me in a phone interview. He said it sits there with the other “treasure” in his life: a baseball signed by Mickey Mantle. He plays down what he did to win it. “The incident itself lasted maybe sixty seconds,” he said. “It was just a thin little sliver of my life.”

Here’s how Ernst describes the lead-up to what happened that December day in 1989:

“I was driving west on Clifford Avenue near Hudson when I noticed smoke pouring out the side window of a house. The fire department wasn’t there. I pulled my truck to the side of the road, got out. Smoke was pouring from around the front window, and through the window I saw an orange glow and small hands banging against the glass.”

Inside the house, in an apartment on the first floor, were two young children, Charles Troche, age 2 and his sister, Nina Troche, 6 months old, as well as their mother.

In its commemoration of Ernst’s action, the Carnegie Hero Fund describes what happened next:

Seeing hands in a window of the bedroom, Ernst pulled himself up to the level of the window and broke out its glass. Despite dense smoke in the room and flames spreading nearby, he climbed into the apartment and, with visibility virtually obscured by smoke, found Charles about eight feet away. He took Charles to the window and handed him to a person outside, then turned back into the room and found Nina and the children’s mother on the floor. Ernst took Nina to the window and handed her outside, then attempted to save the children’s mother. Arriving firefighters removed the mother and another of her children from the bedroom.

Nina and Charles were treated at a hospital for smoke inhalation, and they recovered. Ernst also required hospital treatment for smoke inhalation and for cuts to his hand, and he too recovered.

The next day the Democrat & Chronicle ran a story, “RGE Man Saves Kids from Fire.” The city Fire Chief nominated Ernst for a Carnegie Hero Award. Ernst doesn’t recall there being a ceremony; the medal just showed up in the mail with a letter and a check for $2,500. At an event one year later, Ernst had a brief visit with the family of the two children he’d saved, but they didn’t keep in touch.

At the time of the fire, Ernst as his wife had two young children: one three years old, the other just three weeks. Two of the Four Chaplains, when they sacrificed their lives, also had young kids: Clark Poling, the Dutch Reform minister, had a young son and pregnant wife; Alexander Goode, the rabbi, had a 1-year-old daughter.

“Did you have any sense during those few minutes of putting yourself in danger?” I asked.

“It’s an interesting question, Peter,” but no, I didn’t. When something needs to be done, when there’s distress, you don’t stop to think about that. You address the problem at hand and then when all is done, you just thank God that you made it through–because I probably shouldn’t have.”

And many don’t make it through. Twenty-five percent of Carnegie medals are awarded posthumously.

So where did your motivation come from? I asked.

“The whole thing was a testament to my father who–you’ll have to excuse me if I get emotional—who taught me to do the right thing. My dad was a man of action, somebody who couldn’t sit and watch. He took on every lost cause, righting wrongs and taking care of people in distress.”

‘You were 31 when you rescued those kids,” I said. “Being older now, any change in your thoughts about the whole thing?”

“Of course, your perspective changes from age 31 to 63. For me, those sixty seconds on a morning in December were a very personal event, but now I think of how many people grasped onto it and made news of it. I was brought to meetings with important people; everyone seemed to revel in the event more than I did. I wasn’t a hero—I just reacted to a situation where people needed help. But I think everyone else needed a hero.”

Ernst hadn’t heard of the Four Chaplains.

Could we have a national hero today? I asked.

“No, I don’t believe so,” he said, without hesitation. “The problem is our definition of hero has changed.”

Ernst told the story of World War II hero Audie Murphy.

“Murphy was a little guy, like me—I’m five foot three. He jumped off a burning tank in the heat of battle and held off a German division single-handedly. He put his friends’ lives ahead of his own. That was the definition of a hero: someone who put others ahead of themselves.

“But, today,” he continued, “I don’t know if that’s even admired. Soldiers who had done wonderful deeds in Iraq and Afghanistan to preserve their friends’ lives were treated badly when they got home, as if they were evil.”

“Today—and this is part of the social media thing—victims and criminals are made into heroes. They say a hero is somebody who unites everybody, but we are so shattered as a society that there’s no one person who would be defined as a hero by everybody. We’re all in our own little worlds and we all have our agendas. I just don’t know if there’re any heroes left.”

I told Ernst that’s what I’m searching for.

“Are you finding any?” he asked.

“I found you,” I said.

“We need heroes,” said Ernst. “And I’m not even saying I was one. But we need someone to admire, to look up to. If we don’t have heroes, there’s a void. But as far as any specific person today, I can’t really name one.”

I tried to locate the two children—now grown to adulthood—whom Ernst had saved thirty years ago. I wanted to learn from them what that experience was like, how it may have inspired them. Despite a good amount of digging, however, I was not able to find them.

But I did find someone else: a young woman who, as a girl, was saved from a burning home in Rochester by another Carnegie hero. That’s how I met Jacque Woods and why in August she and I visited the weed-covered lot where her family’s home once stood.

The pain passes but the beauty remains

Pointing to a grassy area about 10 feet further in from where Jacque and I stood, she said, “Our bedroom would have been right there.”

Back then, she was Jacque Thompson, age 4, and in that spot was the bedroom she shared with her 1-year-old sister, Rebecca.

“Was there a window in your room?” I asked.

“Yep. It faced this way,” she said, pointing to Aab Street. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve cried. Why couldn’t I get my sister out the window? But I was 4 years old. How am I supposed to—

“But, Jacque, you weren’t even awake. Jim woke you up.”

“Right. I know that. I know that as an adult, but in processing the trauma I used to carry that guilt pretty heavily for Rebecca.”

She pointed to the outdoor playground at the school next door.

“I have very vivid memories of playing with Becca on our swing set; she had a little baby swing. You think about a playground being right there and kids the same age as I was when my journey started here. They’ll never know…”

Here’s how the Carnegie Hero Fund describes what happened to Woods and her sister the night of April 27, 1991:

Jacqueline, 4, and her younger sister were in their bedroom when, early in the morning, fire erupted in the adjoining living room of their family’s one-story house. (James A.) Auble, 36. . . was in the neighborhood when he was alerted to the fire by the screams of the girls’ mother. After learning that the girls were in the house, Auble entered through the front door and passing through the burning living room, reached the bedroom. He removed the girls from their beds and began to retrace his steps, using the wall to guide him. Fire conditions were worsening and in the blistering heat, Auble fell to the floor of the living room, losing his grip on the girls. He fled the house, as did Jacqueline.

Jacqueline required hospitalization for severe burns, and Auble also required hospital treatment, for second-degree burns to his hands and knees. He recovered. Jacqueline’s sister died.

Woods filled me in on some of the details:

The fire had started in a ceiling fan in the living room that her parents had left on. “It was the end of April, a warm night. I mean, I don’t think that’s a bad thing, you know, to leave the ceiling fan on to get circulation. But then the wires got crossed and sparked up.”

Her sister, Rebecca, was deceased when she was brought out of the house. “They say she died in bed from smoke inhalation before there were a lot of flames.”

Woods was taken to Strong Memorial Hospital where she spent months in the burn unit and then in pediatric care. She retains burn scars on her right arm, leg, and thigh. “They’re not full circumference, though, because they happened in bed while I was sleeping, and I was sleeping on my left side.”

Her rescuer, Jim Auble, worked for the Democrat and Chronicle. He’d been out early dropping off bulk papers when he spotted smoke and flames. “Jim 100 percent saved my life,” said Woods.

Soon after the fire, Woods and her parents met Jim Auble but then fell out of touch. Later, when Woods was 11, her family received a letter from Auble. He’d married and had children. Wood’s parents invited the Aubles for dinner. The families became friends. “We’d go over to their house on Sunday for dinner or to watch football,” Woods recalls. Later, she babysat for the Aubles’ three children.

There are almost no aspects of her life, Woods told me, that have not been influenced by Jim Auble’s heroism.

Psychologists say age three or four is when the “ego ideal”—the image of what or who we aspire to be—begins to form in children, and that’s exactly the age Woods was when Jim Auble saved her life. Perhaps as a result, Woods grew up aspiring to become a nurse. Later, she joined the Army National Guard as a medic.

In 2007, when Woods was ready to leave for boot camp, her parents threw her a going-away party, and though he was then ill with cancer, Jim Auble attended. He gave her a gift. “He’d made me a video,” she says, “telling me how proud he was of me.” She keeps the video on a flash drive.

Auble died soon after but remains an inspiration to the woman whose life he saved.

“In the morning during basic training,” Woods recalls, “we’d have to run these ridiculous hills and I’d be like, ‘I don’t want to do this. Why am I running?’ And then I’d think, ‘I’m doing this for Jim because he put his life on the line for my life, for me to have purpose.’ I didn’t see it as a negative like I owe him. I saw it as a motivation, like I owe it to him to live the best life I can live and do the most that I can with it.”

Woods served for eight years in the Guard and later as an emergency medical technician, but eventually found that to make a living she would need to find other lines of work. Today, she lives in Kansas City, Mo., and works at a private firm as a manager in transportation logistics. She is divorced and has a 5-year-old daughter, Adalyn, whose middle name is Rebecca.

Earlier that day, before our visit to the site of her former house, Woods and I met for coffee. We talked about heroism and about the Four Chaplains. She was not familiar with them but was intrigued by the story.

Can we have heroes today or is the country too divided? I asked.

“I think the definition of hero and heroism has changed,” she said, echoing what Kurt Ernst had told me. “It used to be it was about putting your physical life on the line, but nowadays if you just stand up for whatever you believe in, you’re considered a hero.”

“But it seems to me,” I said, “that most people today would still agree that what Jim Auble did was heroic.”

“Absolutely,” she agreed. “You put your life on the line, and you run into danger without second-guessing the consequences to yourself. Whether life comes out of it, or death comes out of it, it was still an act of heroism. So, I lived; my sister passed away. He ran into the face of danger; he’s still a hero.”

I asked who she thought might be able to be accepted as a national hero today.

“I don’t feel like we’re at a place in time where everybody would accept somebody. There’s just so much division. It would take a movement of people to be able to step back and realize there’s bigger things in life than themselves.”

Is social media a factor?

“I hate social media with a passion!” she said. “I think it causes more divisions than anything. It’s a path of ignorance to where people see a meme or a post on Facebook and they think that’s the truth.

“If Jim Auble had lived during a period of social media—” I began.

“Well, first of all he wouldn’t have been delivering the newspaper!” she quipped.

“Good point. But if somebody has been reinforced in their own self-focus as you describe, would they be as inclined to do something like Jim did?”

“It bothers me when I see videos on social media of people with their cellphones recording something instead of taking action. Like, you see video of a little boy standing on a rock in the middle of a raging river, and a hundred people stand around with their phones recording it and maybe just five try to help him. Those hundred standing around—what’s their mindset? It stirs something in my soul and bothers me.”

After more than 30 years, Jim Auble’s heroic act still motivates Jacque Woods to live “the best life” she can. As her tattoo says, “The pain passes but the beauty remains.”

But we are a nation of 330 million. There are not now and there never will be enough Carnegie medal winners for everyone to have their own individual hero—nor would we wish anyone to suffer the type of tragedy to which heroic rescuers typically respond.

Instead, we need what we have always needed—what every society has needed since ancient times—heroes who are nationally recognized and accepted, who can elevate us all emotionally, expand our sense of the possible, and inspire us to live our best lives.

The search for them, I think, is worth continuing.

Peter Lovenheim, journalist and author of “In the Neighborhood” and “The Attachment Effect” is Washington correspondent for the Rochester Beacon. He can be reached at [email protected].

I received a Carnegie award from the Scottish Trust Fund quite some years ago, so I can empathise with this wonderful person. Well done, and may you always have light in your life.

Thank you for your thoughtful peace. If I could nominate 3 people who should be consider heroes in our society I would suggest Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche and Ricky John Best who stood up to a man who was verbally attacking Muslim girls in Portland, OR when they were stabbed to death defending the girls. I would also suggest Eugene Goodman, the Capitol police officer who bravely and wisely led insurrectionists away from congress.

Another wonderfully enlightening Peter Lovenheim piece. I think and learn every time he writes…..

Peter, look no farther, travel no more. Pre-vaccination, every hospital and doctor’s office employee who went to work is, in my book, a hero even as, if you ask them, they will all decline the honor….